Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

What is Real (The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics)

Author: Adam Becker

Narrated By: Greg Tremblay

Adam Becker (Author, science writer with a PhD in astrophysics from the University of Michigan and a BA in philosophy and physics from Cornell.)

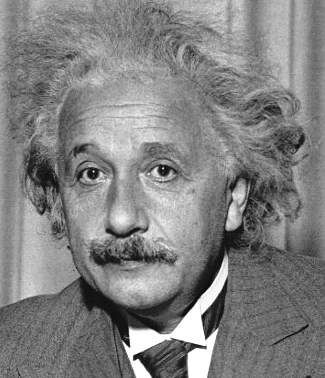

This is an excellent story about the meaning of quantum physics even though the answer remains elusive. Becker does a great job of revealing the personalities of great physicists of the twentieth century, i.e. Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, Erwin Schrödinger, David Bohm, Werner Heisenberg, John von Neumann, Hugh Everett III, John Bell, and to a lesser extent, Paul Dirac, and Grete Hermann.

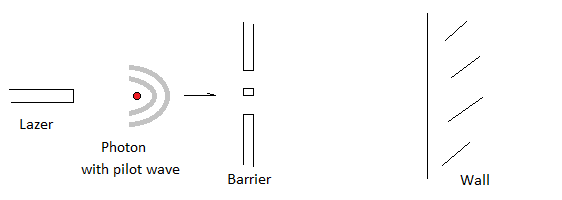

Bohr is shown to be a brilliant person who gathers the luminaries of physics around him like a queen bee to a beehive. Surprisingly, Becker notes Bohr’s abstruse and convoluted verbal and written explanations of physics cloud his brilliance but fascinate and inform young scientists. In contrast, Einstein appears like a sun that physics’ luminaries revolve around. Einstein never accepts the idea of quantum physics that implies we live in a probabilistic world. David Bohm is a brilliant physicist exiled for his political beliefs but importantly theorizes the Pilot-wave theory for quantum physics that suggests wave collapse is immeasurable and therefore meaningless. If true, the “cause and effect” world insisted upon by Einstein is correct. Surprisingly, Einstein demurred but the theory is being resurrected by Logical Positivist today.

Though Heisenberg creates the idea of Quantum theory that argues for a probability world, he becomes a Nazi science leader who fortunately fumbles the mathematics that could have created an atom bomb for Germany during WWII.

As a protege of Bohr, the theory of a Quantum world takes hold of scientists. John von Neumann is shown as a mathematical genius who challenges Bohm’s Pilot-wave theory because quantum mechanics appears to work and is proven by experimentation. Bohm argues, like Einstein, that the universe is fundamentally knowable and deterministic, not probabilistic. Hugh Everett III is taken under the wing of John Wheeler who is Everett’s PhD advisor at Princeton. Everett is characterized as a brilliant student who takes the idea of the disappearance of a collapsed quantum particle not as a collapse but an entry into another world, another dimension of reality.

Having read and partly understood many books about physics, Becker’s history is most entertaining because of added information about physicists’ personalities and disagreements, along with their personal trials and tribulations.

An added benefit is a little more understanding of physics that is offered to dilatants of science like this science ignoramus.

Pilot Wave Theory suggests the collapsing wave shown by quantum experiments is of no concern and that it should be ignored as a factor for non-predictability.

Putting aside collapsing waves in theoretical physics, the pilot wave theory, also known as Bohmian mechanics, was the first known example of a hidden-variable theory, presented by Louis de Broglie in 1927. Its more modern version, the de Broglie–Bohm theory, interprets quantum mechanics as a deterministic theory, and avoids issues such as wave function collapse, and the paradox of Schrödinger’s cat by being inherently nonlocal. This nonlocal experimental proof violates Einstein’s physics beliefs.

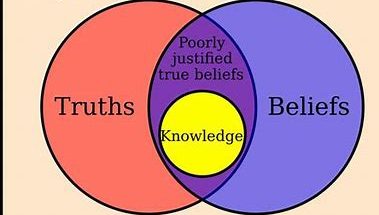

As one goes back to Bohm’s Pilot-theory. The surprising reveal in Becker’s history is the growing belief in Logical positivism which suggests the argument for quantum mechanics is flawed. The inability to measure both position and momentum is not proof of the theory because it is not an observable phenomenon. In a backward sense it implies Einstein is still the sun around which physics scientists orbit. An irony is that Becker believes Einstein would not want to be considered a Logical Positivist.

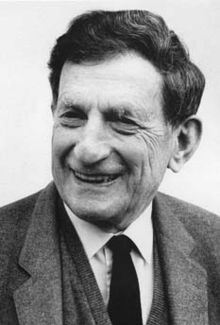

John Stewart Bell (1928–1990) was a Northern Irish physicist whose work reshaped the foundations of quantum mechanics.

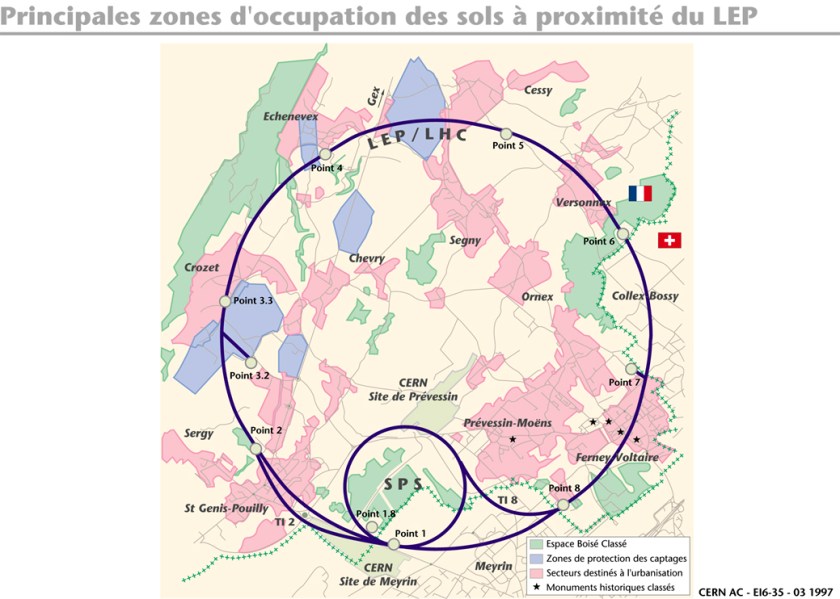

Bell is best known for formulating Bell’s Theorem, a landmark result that showed how quantum mechanics predicts correlations between entangled particles that no local hidden-variable theory can explain. In one sense, that theory suggests as Einstein believed, that there is an undiscovered theory that will return physics to a cause-and-effect world. However, belief in non-locality is something Einstein could not accept. He refused to believe in “spooky action at a distance”. Bell was born in Northern Ireland. His fascination with science led him to CERN in Geneva where he worked on foundational questions in quantum theory.

Bell’s work laid the groundwork for quantum information science, including quantum computing and cryptography.

Bell came from a modest background and rose to prominence through sheer intellectual brilliance. He worked at CERN in Geneva, where he pursued foundational questions in quantum theory as a kind of “hobby” alongside his main work in particle physics. His 1981 paper “Bertlmann’s Socks and the Nature of Reality” used a quirky analogy to explain quantum entanglement and the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen paradox.

Bell wasn’t just a theorist—he was a philosopher of physics in the deepest sense, asking what quantum mechanics tells us about the nature of reality itself. Bell derived mathematical inequalities—called Bell inequalities. He believed that any local hidden-variable theory must obey these inequalities. However, quantum mechanics predicts violations of these inequalities under certain conditions. Bell is reintroducing the belief that quantum particles are fundamentally probabilistic and interconnected in ways that defy classical intuition. The universe doesn’t follow the rules of local realism. Quantum mechanics is correct, but it’s weird—deeply weird and challenges Einstein’s belief that physics are a local phenomenon that will be predictable based on an undiscovered truth.

Logical positivism and Bell’s Theorem intersect in a fascinating way. Bell’s Theorem challenges some of the foundational assumptions that logical positivists held about science, meaning, and reality. Because of “spooky action at a distance”, his theory defies Einstein’s belief in locality and reintroduces the concept of unpredictability which Einstein refuses to believe.

As a philosopher, Hermann (19o1-1984) had a particular interest in the foundations of physics. In 1934, she argues for a conception of causality with a revised view of quantum mechanics. Her work reinforces Einstein by returning Quantum Physics to predictability and causality. Hermann concludes–despite experiments that showing quantum mechanics are probabilistic, the theory is wrong because of a misunderstanding of nature. This seems like a cop-out supporting Einstein’s belief that there are some undiscovered laws of physics.

Becker does not tell listener/readers anything new about reality in his book, but he outlines the difficulty Physics is having in trying to discover “What is Real”. For this reviewer, Einstein remains the sun around which Physics’ scientists revolve.