Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

SHARP (Simple Ways to Improve Your Life with Brain Science)

By: Therese Huston PhD

Narrated By: Theresa Bakken

Therese Huston (Author, earned an MS and PhD in Cognitive Psychology from Carnegie Mellon University.)

Therese Huston is a well-known public speaker who has written a book that has appeal for those who wish to know what they can do to improve their memory and cognitive abilities. This is not a book some will be interested in either listening to or reading. Many presume they have a proscribed intelligence and memory largely determined by genetic inheritance. Huston infers there is some science-based truth in that opinion but that one’s memory, cognitive ability, and psychological health can be treated, if not improved, at any age.

Huston’s prescription for improved memory and cognitive ability requires effort.

Undoubtedly, we inherit much of our innate cognitive ability but whatever one’s genetic inheritance and age may be Huston argues cognition and memory can be improved. Huston discusses areas of the brain that are the base from which cognition and memory originate, are stored, and then called upon.

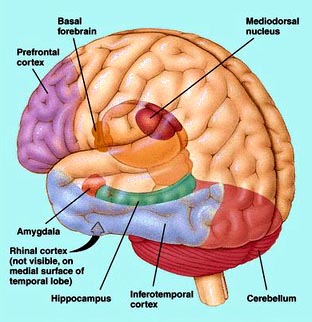

Huston notes the hippocampus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex, neocortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia are key brain areas involved in cognition and memory.

The hippocampus is the primary location of memories, but the other five areas interact with one’s personal experiences in ways ranging from emotion, individual understanding, decision-making, reasoning, skill development, and formed habits. As we age, the way we process, store, and retrieve information deteriorates. We lose some memories, process information more slowly, and find it more difficult to process new information in the context of past experience.

What Huston explains is that exercise, visual, and tactical experience can improve memory and cognition at every age.

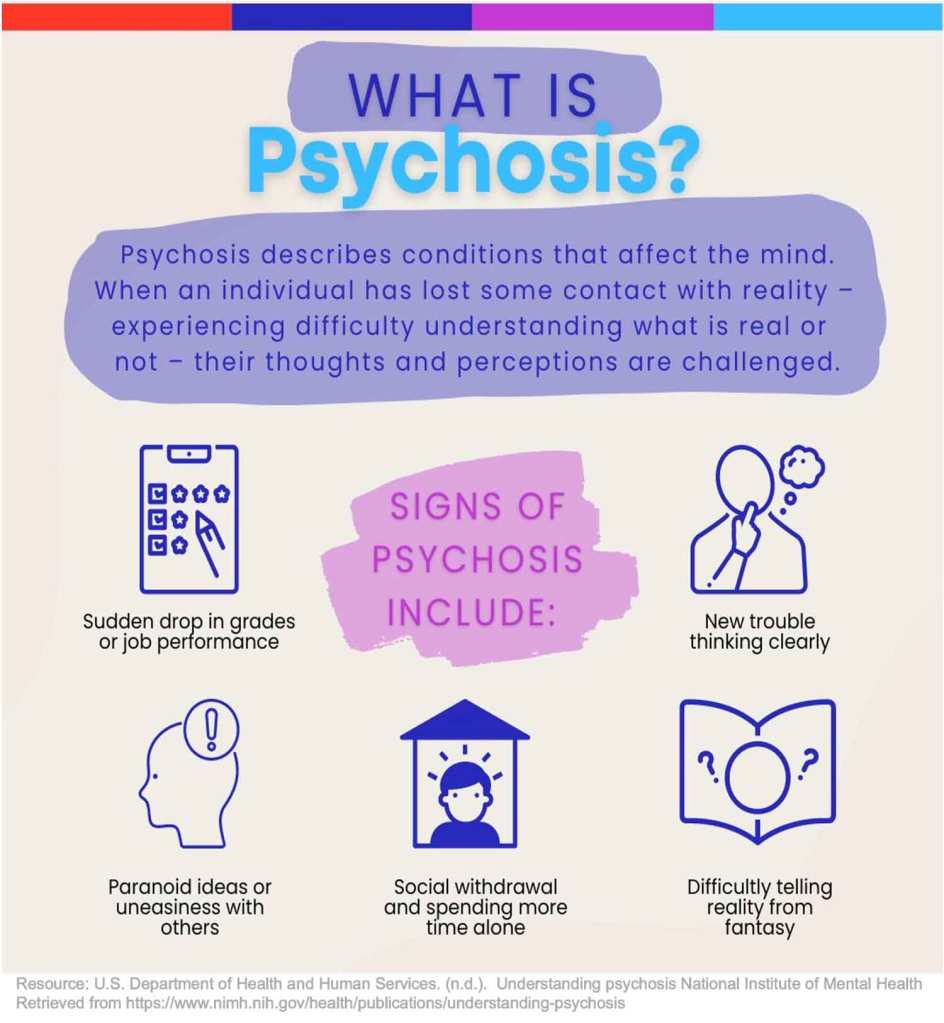

Staying active, experiencing the world in ways that stimulate the production of dopamine, and exercising effort to learn and do new things improves cognitive ability and memory. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the human body that regulates mood, focus and behavior. It is released by the body when it is stimulated by exercise, engaging experience, and learning new things. Huston offers advice on how one at any age can improve their mental health and care for themselves and others when they are troubled by various common and extraordinary events in life. Life’s events stimulate the release of dopamine which can illicit rage and bad behavior but also provide focus and beneficial behavior.

Huston suggests 14 generally simple ways of helping oneself and others cope with the stresses of life.

Many of her solutions are commonly understood, others less so. Not surprisingly, she notes exercise, proper nutrition, quality sleep, and deep breathing are important for maintenance and improvement of brain function and memory. Some more difficult and less understood aids to brain health and memory are 1) importance of social engagement, 2) learning new things from personal and other’s recorded experience, and 3) practicing ways of reducing the stresses of life in yourself and others you care about.

One who reads or listens to “Sharp” will recognize the value of Huston’s advice for improving memory and cognitive ability.

After two or three chapters, reader/listeners will likely complete her book. The difficulty, as with all good advice, is following it.