Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

“Moon walking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything“

By: Joshua Foer

Narrated by: Mike Chamberlain

Joshua Foer (Author, freelance journalist, 2006 USA Memory Champion.)

Joshua Foer offers an interesting explanation of human memory. Foer became the 2006 USA memory champion. Foer explains how he achieved that distinction. What is interesting and surprising about Foer’s achievement is that he argues extraordinary memory is a teachable skill.

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930)

Fans will remember Sir Arthur Conan Doyles’ explanation of Sherlock Homes’ prodigious memory technique called the “mind palace”.

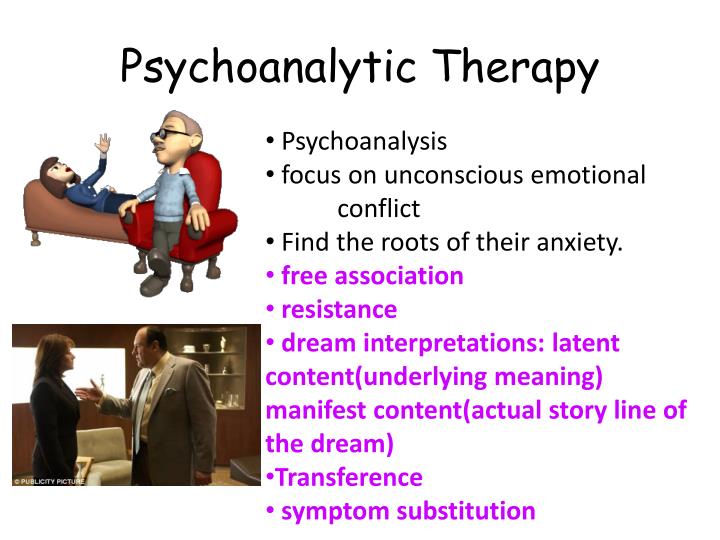

Foer explains the idea is not a fiction but an historically proven method for improving one’s memory through association. “Mind palace” is traced back to ancient Greece as a memory tool of the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos. The idea is to associate facts with familiar features of a house in which one has lived, or of which one has intimate knowledge. The idea of memory being associated with something is not revelatory to anyone who tries to remember someone’s name. Many people, particularly good salespeople, use association to remember a customer’s name. They might remember Fred as a “red” tie or Monica as a “harmonica” and so on.

The problem is recalling a mind’s recorded information. If one makes a point of associating a fact with something that is familiar, say like a space in your own house, it is more likely to be recallable. Foer notes experimental studies show human brains record memories of events but may be unable to consciously recall details. In “show and tell” experiments, humans show evidence of a recorded memory by expressing familiarity, if not specificity. (“MIT research explains how our brain helps us remember what we’ve seen, even as visual information shifts around within our visual system.” See MIT NEWS Feb. 8, 2021.)

Foer suggests the history of memory began naturally with tales told and re-told before writing became a way of record keeping.

Foer explains history shows that philosophers like Socrates rejected the idea of recording information as a way of revealing truth. To Socrates, truth comes from conversational exploration of nature as it is. Foer suggests society is fortunate that Plato and Archimedes partly disagreed and chose to provide a written record of Socrates thought.

From an oral tradition to the written word to radio to television to the internet of things to microchips in one’s brain–the recall of facts become more widely shared. The complication of improving “knowledge leveling” is in how recalled facts are assembled by the brain of the receiver.

Foer illustrates how much effort must be put into memorizing information if one wishes to excel as a technologically unplugged person who wishes to recall more facts. It requires concentrated effort to create a mnemonic device like rooms in a house to associate a series of facts or numbers that can be recalled. On the other hand, advances in technology could make that exercise moot.

In the near future, recollection from an implanted human chip could improve correlation of facts for thought and action.

This is not to diminish the accomplishments of the author in training his mind to recall facts better than others. In the near future, recalling and collating facts may be more efficiently managed by an A.I. microchip that complements human thought and action.

Having eidetic memory or technological total recall does not make humans more intelligent or necessarily more informed about the world. Recall of facts is only a means to an end that may as easily destroy as improve society.