Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

“Master, Slave, Husband, Wife“

By: Ilyon Woo

Narrated by: Janina Edwards & Leon Nixon

Ilyon Woo (American author, Received BA in Humanities from Yale College and has a PhD in English from Columbia University.)

“Master, Slave, Husband, Wife” will disabuse any listener who may think the American Civil War was not about slavery. Ilyon Woo’s detailed research of Ellen and William Craft reveals the many reasons why no one can deny the fundamental cause of the Civil War in America, i.e. it was slavery.

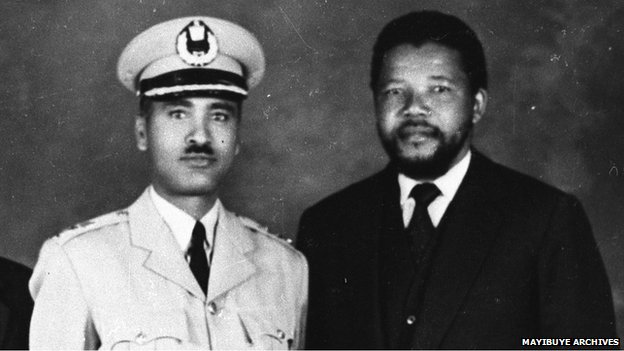

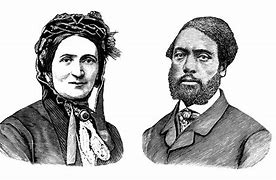

Ellen and William Craft

Ellen and William Craft were slaves until escape from their slave master in 1848. William was enslaved by a white land holder named Robert Collins who held a half interest in Craft’s ownership with another southerner. Ellen was the child of a white owner and black slave that gave her a fair-skinned white racial appearance. However, Ellen was classified as a slave because of her mixed racial parentage. Her mother was a slave to a white slaveholder who was her putative father. At the age of eleven, Ellen was gifted as a valued piece of property to a sister who later became Collin’s wife.

Ellen missed her birth mother but only after years of being on the run, did she manage to re-unite with her mother, Maria Smith.

In 1846, Ellen reached the age of 20 and agreed to marry William who was a skilled cabinet maker.

William was allowed to work for a portion of his wages in return for a cut of his income to be paid to his owners. In 1848, with the money William saved from his outside work, the married slaves planned an escape from Collin’s household. The plan was for Ellen to dress herself as a white man with William as her slave on a journey to Philadelphia, Boston, and possibly Canada.

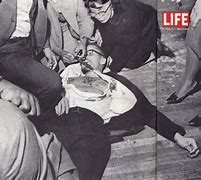

Ellen Craft dressed as a white man with an accompanying slave who is actually her husband.

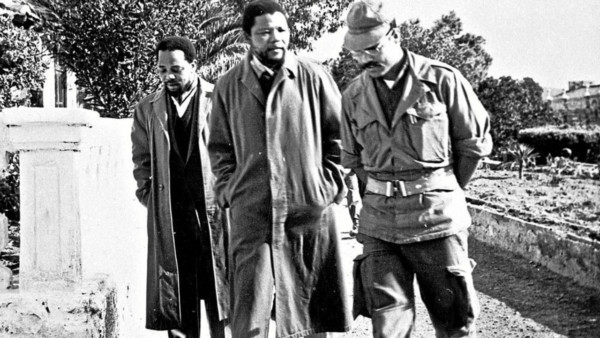

The fugitives succeed in their escape, but their success is challenged. The challenge came from the morally misguided attempt by the American government to avoid a war between the North and South by passing the “Fugitive Slave Act of 1850”.

That act would allow capture and return of runaway slaves to their putative owners. The Act was a compromise between the north and south, supported by President Millard Fillmore, who was willing to sacrifice black Americans to slavery in order to preserve the Union. Storied and respected leaders of America like Daniel Webster, who had freed his slaves, supported the “Fugitive Slave Act”. Webster believed, like the majority of a white Congress, that union was more important than human equality.

Woo’s detailed research reveals how Ellen and William had both black and white supporters who recognized the iniquity of slavery and helped them escape bounty hunters hired by Robert Collins to return the Crafts to slavery. Ellen and William were in Boston. They were helped to escape by Boston’s anti-slavery Americans of conscience.

The anti-slavery movement extended into some of the city of Boston’s government officials. Some local government officials refused to cooperate with bounty hunters trying to fulfill the legal requirements for recovery of escaped slaves. Woo infers Boston boiled with demonstrations against the “Fugitive Slave Act”.

The danger of recapture remained palpable because some officials were concerned more about preservation of the union than the iniquity of slavery. Ellen and William chose to flee to England. Their escape is aided by Quakers and the support of famous black Americans like Fredrick Douglass and William Wells Brown. Douglas publicized the story of the Crafts. William Wells Brown, an equally famous slave escapee, supported the Crafts by using them in traveling presentations that spoke of the iniquity of slavery and how they escaped its clutches. Ellen and William remained in England for 18 years. With the support of Lady Byron and Harriet Martineau, the Crafts learned how to read and write.

The Crafts spent three years at Ockham School in Surrey, England where they taught handicrafts and carpentry.

The Crafts respected each other in ways that defy simple explanation. Though they strongly supported each other, they were often separated for long periods of time. William and Ellen became self-educated writers and teachers who started schools. William traveled to Africa on his own and started a school without his wife. He was gone for months at a time but never broke with his wife who stayed in England.

After 18 years, Ellen and William return to the U.S. The civil war was over. They had five children together with two who remained in England. The Crafts started Woodville Cooperative Farm School in Bryan County, Georgia. The school failed but they continued to farm and wrote a book about their lives titled “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom…” which became popular in both England and the U.S.

The Craft family’s story of their flight to freedom.

Ellen Craft died in 1891. She was buried in Bryan County, Georgia. William Craft died in 1900 but was denied burial in Bryan County next to his wife. William was buried in Charleston, South Carolina. Though separated in death, they seem as tied to each other as they were in life. The Craft’s story is an inspiration for the anti-slavery movement before and after the civil war. Their story reinforces the principle of equality of opportunity for all.