Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

How to Change Your Mind (What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence)

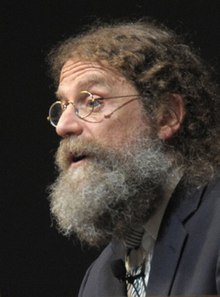

By: Michael Pollan

Narrated By: Michael Pollan

Michael Pollan (Author, journalist, professor and lecturer at Harvard and UC Berkeley, received a B.A. in English from Bennington College and M.A. in English from Columbia University.)

“How to Change Your Mind” is a slippery slope examination of hallucinatory drugs. The slipperiness comes from a concern about drug use even though hallucinatory drugs are not addictive. Written by a liberal art’s graduate rather than a physician, psychiatrist, or scientist makes one skeptical of the author’s review and perspective on LSD and other hallucinatory drugs. However, his story is interesting and has an appeal to anyone who has experimented with hallucinogens.

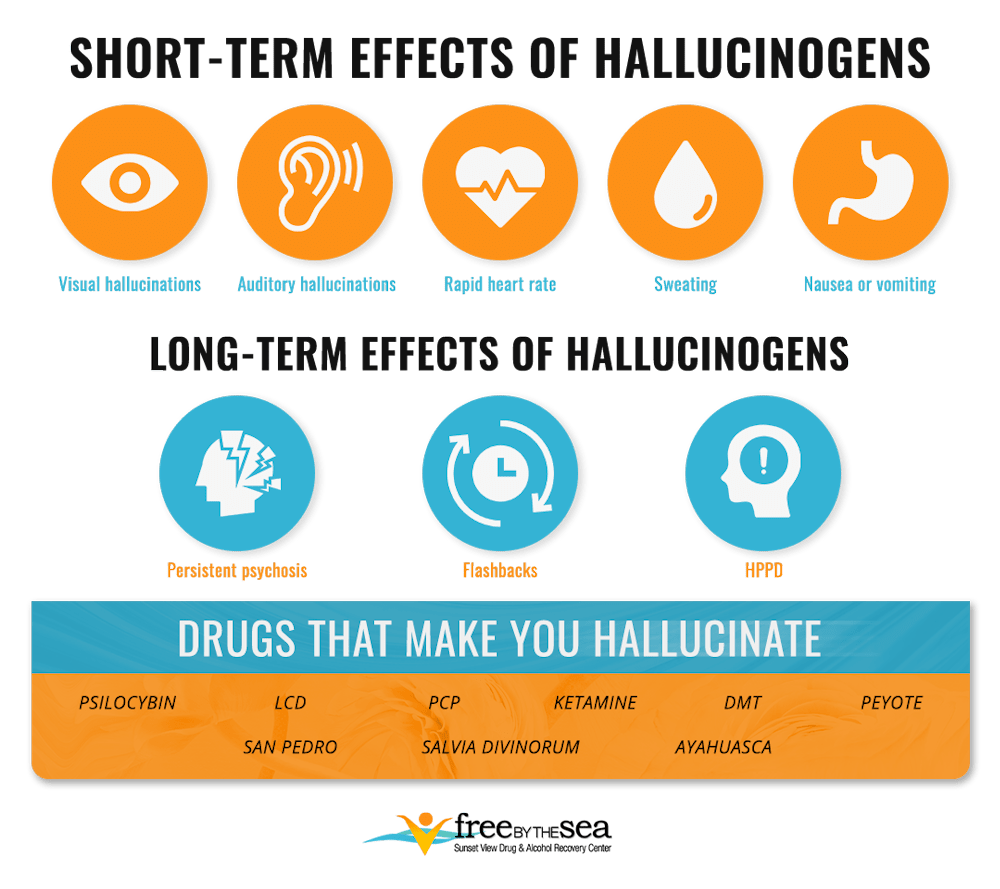

RISKS AND EFFECTS OF HALLUCINOGENS

Pollan’s subject is partly about mushroom drug derivatives, like psilocybin and psilocin, that have hallucinogenic effects. But he also reviews the history of LSD which is a semi-synthetic compound accidentally discovered by a chemist named Albert Hofmann in 1938. LSD is derived from ergot, a type of fungus that grows on rye and other grains.

Albert Hofmann (1906-2008, chemist who synthesized, ingested and studied the effects of LSD.)

Pollan recalls the history of hallucinogenic drugs that evolved from ancient native rituals to public experimentation. Today, medical analysis and treatment with hallucinogenic drugs is being recommended. The revised belief of hallucinogens as a scourge of society is reborn to a level of medical and social acceptance.

One who has lived a long life in the 20th and now 21st century recalls Pollan’s rollercoaster history. Pollan falls on the side of acceptance of the hallucinogenic experience as an aid to society. His reported revisionist belief begins at the age of 60 when he tries a hallucinogenic drug and begins a study of its history. One is somewhat skeptical of Pollan’s objectivity because he is in the business of making a living from writing.

Pollan features several experts in the field of psychedelic research. He refers to Roland Griffiths (upper left corner) now deceased, neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University who conducted studies on psilocybin’s effect on consciousness and mental health. He meets with Paul Stamets (lower left corner), a mycologist who is a fungi guru who explains where psilocybin mushrooms can be found, how they can be identified, while selling hallucinatory mushrooms to become a wealthy entrepreneur. He writes about James Fadiman (right), a psychologist and researcher who conducted hallucinogenic microdosing experiments on patients to show their potential benefits.

Pollan’s history persuasively argues the benefits of hallucinogenic drugs. However, a bad trip can kill you. On the other hand, Pollan notes recent research shows hallucinogenic drugs have alleviated anxiety, depression, PTSD, addiction, and the fear of dying. He notes psychedelics disrupt the brain’s default modes that negatively affect human behavior.

A listener/reader comes away from Pollan’s book with a feeling that there is as much at risk as reward in experimenting with hallucinogens without the aid of professionals.