Audio-book Review

By Chet Yarbrough

Blog: awalkingdelight

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade that Reinvented Philosophy

By: Wolfram Eilenberger, Shaun Whiteside

Narrated by: undisclosed.

Wolfram Eilenberger (German Author, award winning writer and philosopher.)

“Time of the Magicians” is particularly interesting because it tells the stories of four philosophers after WWI when Hitler is beginning his rise to power. Philosophers will undoubtably get more out of this book, but life experiences of these four men make it more interesting to the general public. The primary focus of “Time of the Magicians” is on Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger.

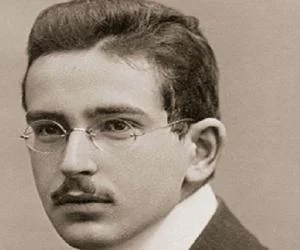

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951, Austrian-British philosopher of logic, mathematics, mind, and language, died at age 62.)

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976, German philosopher of phenomenology, existentialism, and hermeneutics, died at age 86)

Three of the four men who live in “Time of the Magicians” have a Jewish background. The two most famous philosophers are Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger. Heidegger supports Hitler, chooses to join the Nazi Party, and refuses to write or say anything about the Holocaust after the war. The other three philosophers leave their home countries before Hitler becomes Chancellor. Wittgenstein, as a world traveler, becomes a student of Bertrand Russell in 1911 at Cambridge. Walter Benjamin and Ernst Cassirer travel a good deal while choosing to leave Germany in 1933.

One of many interesting points in “Time of the Magicians” is that Hannah Arendt was a student of Martin Heidegger’s at the University of Marburg in Germany.

Despite Heidegger’s antisemitism, at 35 he has an affair with the 18-year-old Arendt who came from a Jewish/Catholic household. This is in the early 1920s, before Hitler’s rise, but it reflects the intellectual compartmentalization of life and human weakness that exists when it comes to sex. (At the time of the affair, Heidegger was married to Elfride Petri in 1917 and remained married until his death in 1976.)

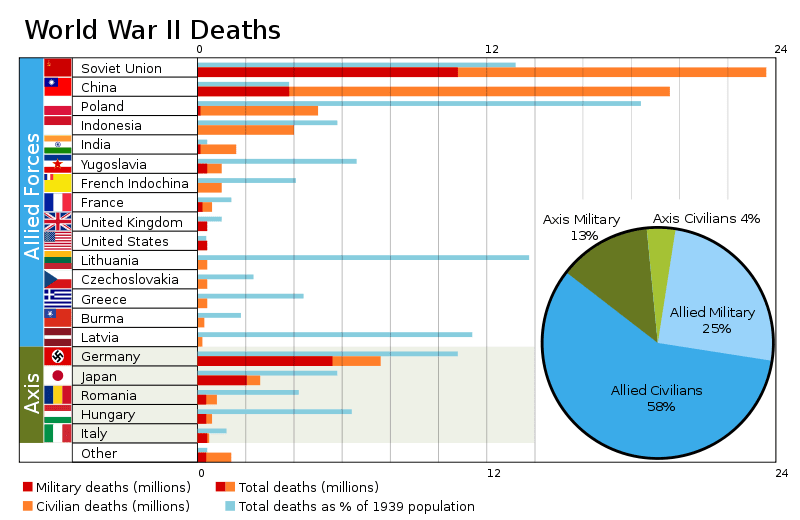

Aside from sexual transgressions noted in “Time of the Magicians”, the biographies of these four men are about their philosophical beliefs. WWI like all wars affects people in different ways. Some, like Wittgenstein, and Cassirer join the military and fight for their countries, while others like Benjamin look for ways to avoid conscription. Heidegger didn’t join the military but served the Nazis as an academic.

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940, German Jewish essayist, philosopher, and cultural critic, commits suicide at age 48)

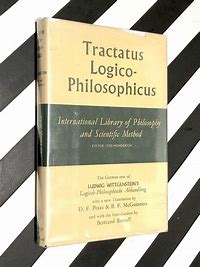

Joining or avoiding military service may come from good and bad motives. Wittgenstein and Cassirer fought for the Central Powers for reasons undisclosed. “Time of the Magicians” suggests Wittgenstein fought valiantly for the Central Powers and became a P.O.W. in Italy. While in prison, Wittgenstein began writing his most famous book on philosophy, “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus”. However, the Central Powers lost to the Allied Powers (the U.K., France, and Russia) in WWI.

Heidegger supported Hitler through the end of World War II. One might conclude joining a war is a bad idea in any circumstance. As some authors have noted, there are no “good” wars. In any case, wars had a great deal to do with the philosophes of these four men.

Ernst Alfred Cassierer (1874-1945, German Jewish philosopher of phenomenology, and culture, died at age 70.)

The experience of war undoubtedly affected all four philosopher’s beliefs. Wittgenstein came from a wealthy industrial family. Wittgenstein is heir to a multi-million-dollar industrial empire. After the war, he chooses to give any fortune he might inherit to his mother, sisters, and brothers. He refuses his wealth and becomes employed in a small town in Austria where he teaches grade school. Wittgenstein refuses any financial help from his family or fellow philosophers. He is mired in poverty that remains his condition until his return to Cambridge.

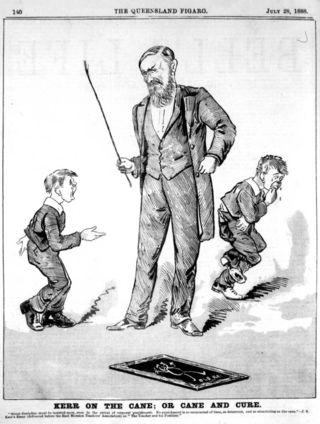

Wittgenstein is characterized as a martinet but committed teacher of his young students.

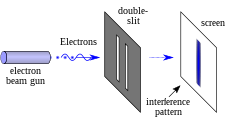

His poverty and isolation seem surreal considering his education and family background. He actually has an engineering degree from the Technical University of Berlin which he received in 1908. His commitment to his young students forms a background to his belief in science with the dissection of animals and his focus on human language.

Today, we take dictionaries for granted, but they were nearly non-existent in Germany after WWI. Wittgenstein begins collecting words used by his students in class to create a dictionary that he intends to have published for schools in his area. The idea is nixed by the school administration.

Wittgenstein leaves the grade school he is teaching after an incident that involves a student who feints after being struck by Wittgenstein. This martial treatment of students is not particularly uncommon, but the parent of the student is a wealthy matron who complains to the school. The school does not discharge Wittgenstein, but he chooses to leave in the middle of the night and abandon his teaching career.

Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus…” is published in 1921 without compensation to its author.

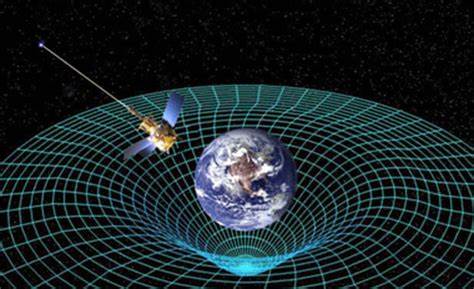

The purpose of the book is to explain the relationship between language and reality. At the same time, it is an attempt to show the limits of science. It is characterized as a difficult book to understand but becomes highly regarded at Cambridge University in England and becomes the basis for Wittgenstein’s return to England where he is called the “God” of philosophy. This is an interesting appellation but equally interesting is the appellation given to Heidegger as the “King” of philosophy. Obviously, both men were highly regarded at Cambridge in the 1920s, but in quite different ways.

“Time of the Magians” is a fascinating glimpse into the lives of storied philosophers and the impact on their understanding of life which appears based on their experience in the “Great War”. War is hell by any definition, but it gave philosophers focus for understanding the meaning of life. Sadly, that understanding did not change the future course of history.