Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Bottle of Lies (The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom)

Author: Katherine Eban

Narrated By: Katherine Eban

Katherine Eban (Author, American Rhodes scholar with a MPhil from University of Oxford.)

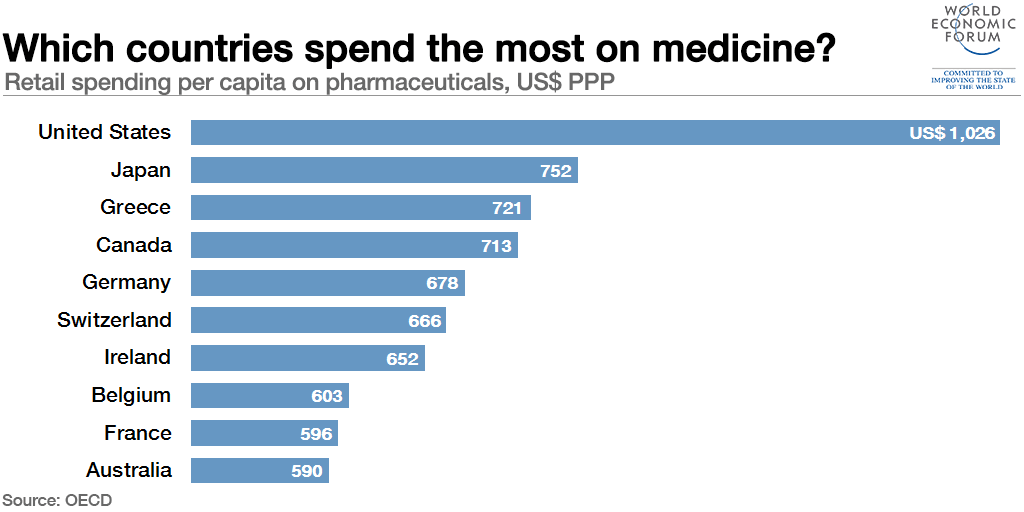

“Bottle of Lies” is a history of duplicity and dishonesty in the generic drug industry. It is a damning dissection of the lure of money at the expense of human life. On the one hand, affordability, healthcare savings, global health, and the value of regulation are made clear in “Bottle of Lies”. On the other, Katherine Eban shows how the lure of capitalism and greed creates an incentive to evade regulation and kill innocent people seeking drug treatment for their illnesses.

Katherine Eban reveals the history of an India drug company named Ranbaxy that was founded by two brothers, Ranbir Singh and Gurbax Singh.

In 1937, these two entrepreneurs recognized the economic opportunity of creating a drug manufacturing operation with lower labor costs in India to capture the market in drugs nearing their patent expiration dates. They were focused more on organizational cost cutting and the money that could be made than the efficacy of the drugs they could produce. The company was sold in 1952 to their cousin Bhai Mohan Singh. This cousin transformed Ranbaxy to a pharmaceutical giant, but his experience was in construction and finance, not pharmaceuticals. However, his son Parvinder Singh joined the company in 1967 and was a graduate from Washington State University and the University of Michigan with a master’s degree and PhD in pharmacy.

Parvinder Singh (1944-1999, became the leader of Ranbaxy in 1967.)

Eban argues Parvinder Singh looked at his father’s business as a scientist with a pharmaceutical understanding and a desire to produce lower cost drugs for the world for more than a source of wealth. Parvinder appeared to value quality, transparency, drug efficacy, and long-term credibility for Ranbaxy. Parvinder recruited talent who believed in lowering costs and maintaining the efficacy of drugs the company manufactured. However, Parvinder dies in 1999 and the executives who took over the company focused on maximizing profit rather than the efficacy of the drugs being produced. Parvinder’s leadership is succeeded by Brian Tempest who expands the company by navigating the regulatory restrictions on generic drug manufacture. Tempest tries to balance profitability with global health efficacy of generic drugs. Parvinder’s son, Malvinder Singh eventually becomes the CEO of the company. He returned control to the Singh family. The corporate culture changed to what its original founders created, i.e., a drug producer driven by profit. Malvinder was not a scientist.

Malvinder Singh (Born in 1973, Grandson of Bhai Mohan Singh and son of Dr. Parvinder Singh.)

Under Malvinder, Eban shows the company turns from science to economic strategy to increase revenues of Ranbaxy. Internal checks on the efficacy and testing of their drugs is eroded. Criticism from regulators and whistleblowers are either ignored or sidelined by company management. Peter Baker Tucker’s role in exposing Ranbaxy is detailed in Eban’s history. With the help of Dinesh Thakur, an employee of Ranbaxy, Tucker bravely exposed the company’s fraud. (Thakur received $48 million compensation as a whistleblower award.) Tucker is an FDA investigator who reviewed Ranbaxy’s internal documents that revealed their fabricated data about their drug manufacturing process.

Peter Baker Tucker (aka Peter Baker, former FDA investigator.)

Ranbaxy is sold to a Japanese company called Daiichi Sankyo in 2008. Eban explains that Malvinder concealed critical information about FDA investigations and data fraud in the company’s sale. Malvinder and his brother, Shivinder Singh, are arrested in 2019 and remain in custody in 2021, facing multiple fraud accusations.

Sun Pharma acquires the remnants of the Ranbaxy-Sankyo’ sale.

Though Eban does not focus on what happens after the sale to the Japanese company, it is sold at a loss to Sun Pharmaceutical Industries and Singh family’s ownership is sued by Sankyo for hiding regulatory issues of the company. Daiichi received a $500 million settlement but effectively lost money on their investment. Eban, in “Bottle of Lies” offers a nuanced indictment of generic drug manufacturer and sale.

Eban believes generic drugs are important for global health because of affordability and accessibility.

Quality and drug efficacy must be insured through international regulation. Eban endorses unannounced inspections, routine testing of the drugs, and strict legal enforcement against poor manufacturing systems. Without transparency and oversight of all drug manufacturing, human lives are put at risk.

This is quite an expose, but it ends with criticism of inspections of China’s drug manufacturing capabilities.

The inspections of foreign companies that manufacture generic drugs, like those she refers to in her book, are conducted by similar inspectors who do not know the culture or language of the countries in which generic drugs are being produced. The FDA was paying their inspector in India $40,000 per year at the time of Ranbaxy’s investigation. It is by instinct, not interrogation, that malfeasance is detected. Too much is missed when one cannot talk to and clearly understand employees of manufacturing companies.

It seems America has two choices: one is to increase the salaries of FDA inspectors and require that they know the language of the countries in which they are working and two, set up a system of random reverse engineering of generic drugs allowed in the United States. This not to suggest all other FDA regulations would not be enforced when a generic drug is proposed but that site reviews would be more professionally conducted. One wonders if anyone who reads or listens to “Bottle of Lies” will take generic drugs if they can afford the original FDA approved product.