Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Locking Up Our Own (Crime and Punishment in Black America)

By: James Forman Jr.

Narrated By: Kevin R. Free

James Forman Jr. (Author, professor of law and education at Yale Law School)

James Forman Jr. argues Washington D.C. is a multi-ethnic democratic example of what is wrong with the American penal system, gun control, and an addiction crisis. Forman offers an eye-opening recognition of America’s social blindness. The 2019 estimated population of Black residents in D.C. is approximately 44%. Forman suggests D.C. constitutes a representative sample of what has happened and is happening to Black Americans in “Locking Up Our Own”.

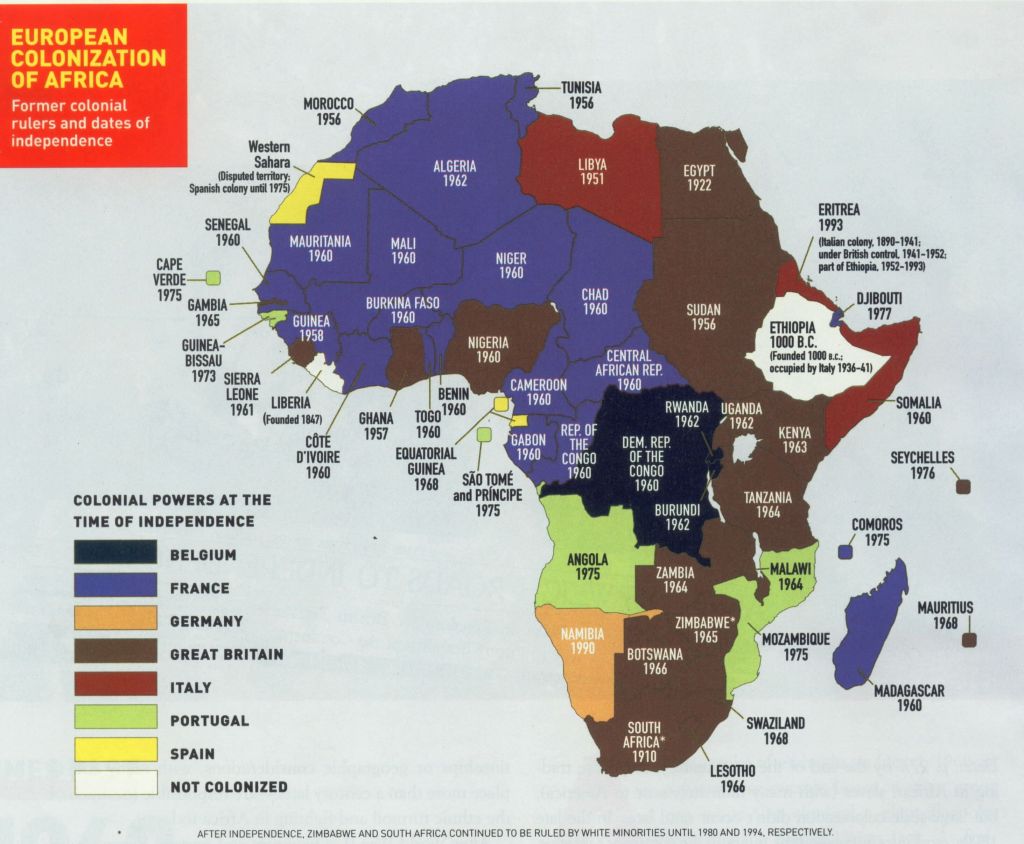

Forman addresses three social issues with Washington D.C.s’ effort to legislate against the consequences of crime associated with a Black population’s gun possession, and drug addiction. America’s history of Black discrimination is well documented. The issues of gun control and drug addiction are top-of-mind issues in all American communities. What makes Forman’s book interesting is his analysis of what he argues is a nascent conservative movement in Black American society.

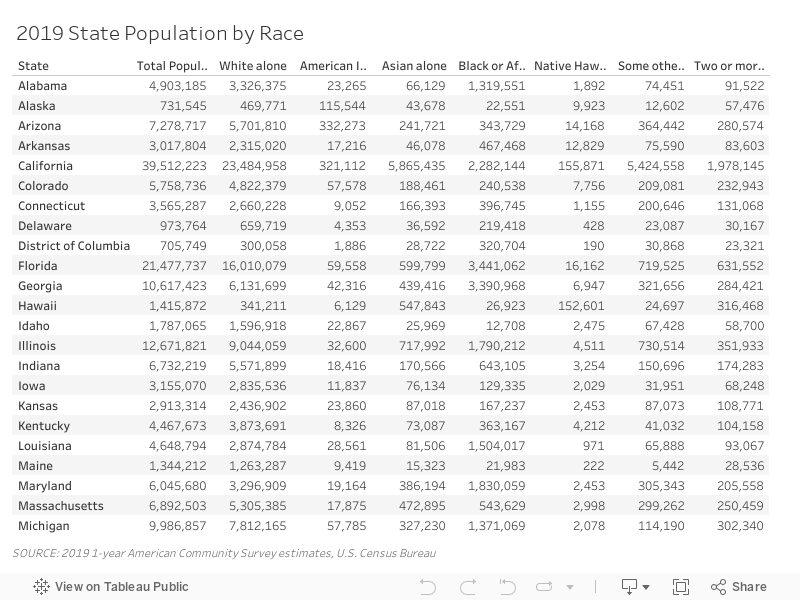

Forman’s argument is based on statistics and the history of Black discrimination. The American incarceration rates for Black citizens are six times higher than for white citizens. Today’s statistics show 33% percent of the prison population is Black when it is only 12% of the U.S. adult population. White prisoners account for 30% of America’s prisoners but amount to 64% of the adult population.

The fundamental issue of Forman’s book is that more Black Americans are being imprisoned for crimes of addiction and theft than those committed by white Americans.

Forman uses Washington D.C. as evidence for a Black conservative movement because of its high percentage of Black residents. He notes D.C.’s effort to legislate gun control and regulate drug addiction are arguably more restrictive than other parts of the country. Firearms must be registered with the police department. A permit is required to purchase a firearm. Concealed weapons require a license. Assault weapons are banned. Magazine capacities are limited. Safe storage requirements are mandated. In the case of addiction, the “Office of National Drug Control Policy”, ONDCP is established in D.C. The program is instituted to provide funding to support communities heavily impacted by drug trafficking. A “Drug-Free Communities Program” offers grants to community coalitions to prevent youth substance abuse. The city expands Naloxone access to citizens to reverse opioid overdose.

Forman explains these policies are supported by D.C. residents in the face of national opposition to gun control. Forman notes the proactive drug control programs of D.C.

The obvious irony of D.C.’s policies is that they do not reflect what white America promotes but suggests Black America is likely more victimized by lax gun controls and drug regulation. White America needs to get on board.

Several chapters of Forman’s book explain the difficulties of integrating minorities into local police forces.

Police department managers opened their hiring practices to Blacks based on growing Black neighborhoods and belief that police services would be improved with officers who would be more racially and culturally suited to understand policing in minority neighborhoods. Forman recounts 1940s through the 1960s police force integration. He notes police department integration is fraught with discriminatory treatment of Black recruits.

Of course, the idea of crime in a Black neighborhood being better understood by Black officers is just another form of discrimination.

Crime is crime, whether in a minority neighborhood or not. Relegating Black police to Black neighborhoods only reinforces racial discrimination. Integrating the police only became another example of racial discrimination in America. Paring white and Black policemen on petrol became difficult. Getting white and Black policemen to work together becomes even more problematic when promotions are denied qualified Black officers. As with all organizations, police promotions were based on experience and standardized testing. What police departments would typically do is promote white officers over Black officers whether their experience rating or test scores were better or not.

The irony of white resistance to gun control and ineffective drug addiction policies has had an adverse impact on Black-on-Black crime.

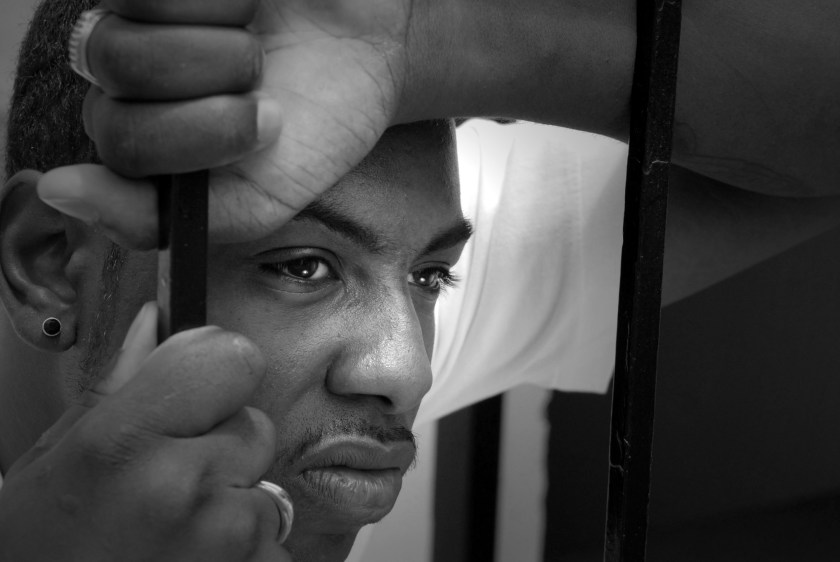

The culture created in formally white police departments adversely condones harsh treatment of minorities. Black officers buy into a police department’s culture and begin discriminating against Black residents in the same way as white policemen.

The 2003 brutal beating and killing of Tyre Nichols by 5 Black Police Officers.

Drug addiction is the scourge of our time. Its causes range from the greed of drug company executives to poor policy decisions by the government to escapist and addictive desires of the public. Addictive drugs are the boon and bane of society. On the one hand, they reduce uncontrollable pain and anxiety; on the other they are often addictive, causing incapacity or death.

Discrimination can only be ameliorated with education, understanding, and governmental regulations that are consistent with the rights written in the American Constitution.

Criminal imprisonment, gun control, and drug addiction solutions are elusive, just as America’s eradication of discrimination is, at best, only a work in progress. Guns in the hands of American citizens are not guaranteed except as noted in the Constitution which infers “A well-regulated Militia…” is the only reason for “…people to keep and bear Arms…” How many more school children have to be killed by guns before the lie of American gun rights is dispelled.

The last chapters of Forman’s book address his experience as a public defender in Washington D.C. This is the weakest part of his story, but it points to the theme of an incarceration system in America that is broken. Prisons are not meant to reform criminals. They are overcrowded, violent, understaffed and, most damagingly, lack rehabilitative programs for re-education and vocational training that could reduce recidivism and return former prisoners to a socially productive society.