Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

The Coddling of the American Mind (How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure)

Author: Jonathan Haidt, Greg Lukianoff

Narrated By: Jonathan Haidt

This is an interesting book written by a social psychologist and a free speech advocate. The authors suggest the focus for parents of Generation Z have, in some ways, become overly protective of their children. They argue– Gen Z’ parents are not addressing the mental health issues caused by this technological age. Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff argue society has become more attuned to children’s protection than the reality of living in a world of diversity.

With the societal change that has accompanied the birth and maturation of Generation Z, immersive tech like AR and VR, along with AI and smart devices, is having profound effects on society.

Haidt and Lukianoff suggest parents focus too much on keeping their children safe to the point of stifling their intellectual growth. The example they give is of the mother who is publicly ridiculed for allowing her 8-year-old son to find his way back home from a city market by mass transit. She prepares him for the excursion with a transit schedule, pocket money, a cell phone, and general information he needs to find his way home. The boy successfully finds his way home and allegedly expresses happiness about what he views as an adventure and accomplishment.

Undoubtedly, there is some truth to the authors’ suggestion that parents are too protective of their children. Thinking of a single mother who has to work but has children at home. Many single parents cannot afford a babysitter, so leaving their children during the day is not uncommon. Single parent families do the best they can but if children are old enough to fill a cereal bowl for breakfast, they are expected to take care of themselves.

John Walsh (Became a child protection advocate, producer, and actor after the murder of his son.)

On the other hand, the writers note the horrible tragedy of John Walsh who’s six-year-old son is kidnapped in 1981. The six-year-old is found two weeks later with a severed head. Though child kidnappings rarely end in such a horrific way, one can understand why many parents became highly protective of their children after the 1980s. Haidt and Lukianoff acknowledge the horrific murder of Walsh’s son, but history shows unsupervised children that are harmed is much less than 1 percent of the dependent children population. What the authors suggest is that some of the overprotection of children since the Walsh tragedy in 1981 has been counterproductive.

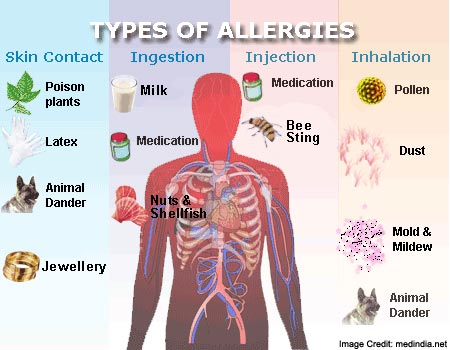

Allergy immunity.

As an example of over protection, the authors suggest peanut butter allergies have risen because of inordinate fear by the public. They suggest that early life exposure to peanuts would have provided immunity and fear of exposure is the proximate cause for today’s rise in allergic reactions. Putting aside the theory of a human body’s creation of developing an allergy immunity, the frustration one has with monitoring a child’s life experience is in knowing where to draw the line between reasonable supervision and overprotectiveness.

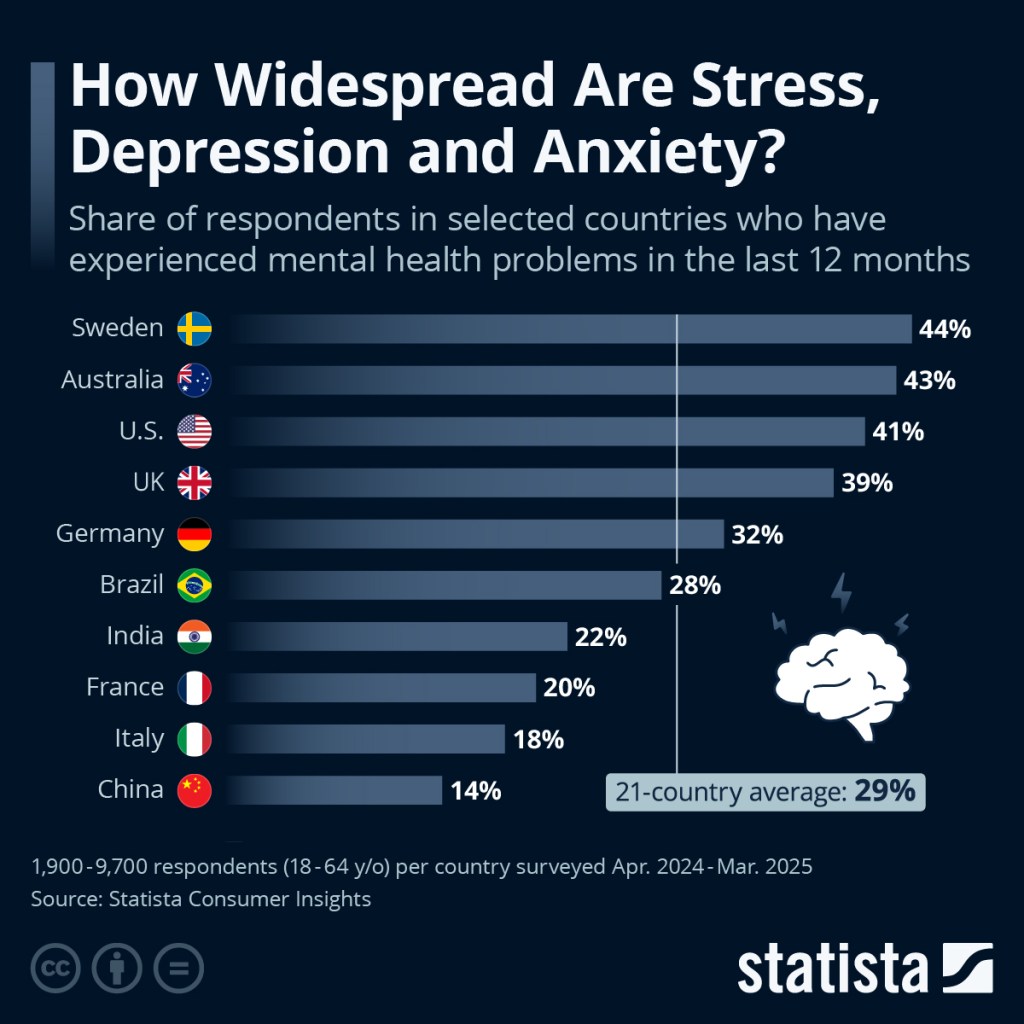

Undoubtedly suppression of free inquiry and play diminishes the potential of a child’s development. Haidt and Lukianoff argue overprotection has contributed to a rising anxiety and depression in Generation Z and society in general. The authors cite national surveys that show increased rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm. They note hospitalization and suicide rates are increasing based on self-inflicted injuries among teens with sharper rises among females. They note colleges and universities are reporting higher demand for mental health services.

Whether stress, anxiety, and depression are because of over protection remains a question in this listener’s mind. One suspects that children are cared for in too many different ways for research to conclude that stress, anxiety, and depression increases due to overprotection. It is more likely due to parental inattention because of work that takes them away from home and personal fulfillment in their own lives which are only partly satisfied by being parents.

Rather than parental overprotection, it seems intensified social media and smartphone use accelerates stress, anxiety, and depression in children and society in general.

Constant connectivity, online comparison, and cyberbullying are having outsized effects on emotional stability. The authors suggest overprotective parenting compounds the negative consequence of connectivity by depriving children of experience that can build their resistance to anxiety and depression. That may be partly true but not the whole story. Smart phone screen addiction takes one away from day-to-day real-life experience. The idea being that experiencing life’s failures and successes builds resistance to anxiety and depression whereas smart screens are pictures of life not lived by the person who is looking at them. Smart phones open the Pandora’s box of judgement which can either inflate or deflate one’s sense of themselves.

A large part of Haidt’s and Lukianoff’s book addresses the public confrontations occurring on campuses and the streets of America that are becoming violent demonstrations rather than expressions of opinion.

They suggest street demonstrations can be used constructively if participants would commit themselves to open dialogue and diverse viewpoints. Participants need to be taught cognitive behavioral techniques that can mitigate emotional reactions while building on psychological resilience. Rather than reacting emotionally to what one disagrees with, participants should focus on diverse viewpoints that allow for disagreement but do not become physical conflicts. We are all an “us”, i.e. not an “us and them’. Confrontation can be the difference between a white supremacist plowing into a crowd in Charleston, South Carolina and non-violent protest by leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. or Václav Havel. People like President Trump see the world as “us vs them” rather than one “blue marble” hoping to find another that can support human civilization.

Peaceful protests are an opportunity to understand human diversity without losing one’s humanity. Race, creed, and ethnicity are who we are and what we believe. Protesters should not be used as an excuse for violence but for understanding. Of course, this is a big ask which is too often unachievable.

The authors believe humanity can do better by allowing children to learn from their experiences while accepting diversity or difference of opinion without violence. Children and adults can be taught by experience and guidance to manage stress. Free play, risk-taking and real-world problem-solving come at every age and they can make a difference in human life. This listener only partially agrees with the author’s belief that “helicopter parenting” is interfering with free play and reasonable levels of risk taking. Democratic cultures need to reaffirm free speech as a mandate; with violence being unacceptable on every side of the aisle.

Anti-Trump demonstration.

Governmental and educational institutions are the foundations of Democracy. They must stand and support the right to free speech without committing, allowing, or condoning violence in the exercise of that right. (Of course, this is easy to say but difficult to follow because of the loss of emotional control by protectors of the public and/or protesters.)