Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Classical Music 101 (A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving Classical Music.)

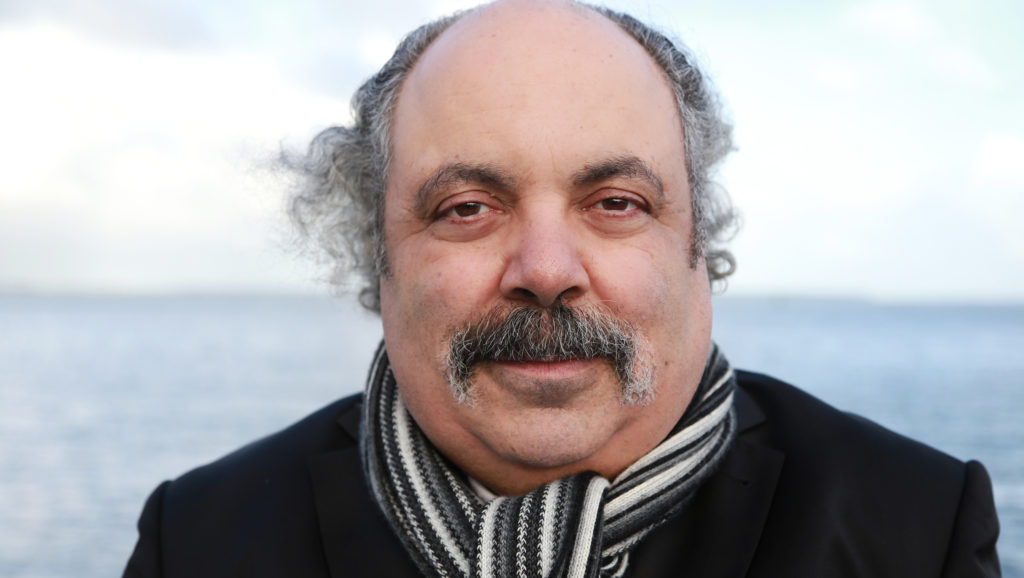

Author: Fred Plotkin

Narrated By: Fred Plotkin

Fred Plotkin (Author, speaker, consultant on food, opera, and Italian culture.)

This is an informative overview of classical music but would have been better if some of the music referred to had been included in an audio version of Plotkin’s book. It is an interesting contrast to Professor Greenberg’s “Great Courses” lectures about classical music. Both writers offer insight to a non-musician’s interest in classical music. Both address Western classical music. They offer sketches of major figures like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and others. Greenberg introduces more information about musical grammar to offer a vocabulary of understanding while Plotkin focuses on how to listen and how modern renditions of the classics can be different from their original performances. The added dimension offered by Plotkin is the emotive qualities of particular musical instruments in a musical production.

Plotkin’s book is a more intuitive introduction to classical music productions than Greenberg’s lectures.

Plotkin’s music review is about the sensual message that classical music offers listeners. Greenberg, though equally insightful, offers a technical explanation of a classical’ composers or performers production. It would have been helpful to hear the difference between an original classical production and a modern interpretation, but Plotkin chooses not to use that audio tool. Plotkin’s high praise for Beethoven’s ninth symphony would have been a welcome audio addition to his insightful book.

Greenberg’s lectures are historical and chronological while Plotkin’s story is more about musical interpretation by different instruments in classical music productions.

Plotkin delves into the change in performances based on newly invented music instruments and different interpretations by performers of classic pieces. A piano began as a harpsichord in the 1700s which plucked strings like those on a tightly drawn bow. This evolves into an escapement that has hammers striking taught strings evolving into today’s pianos. The range of sounds grows with the addition of foot pedals and framed strings evolve from wooden infrastructure to cast iron frames that allow tighter strings and richer sound. (See the review of “Chopin’s Piano“) The number of keys is standardized at 88 by the late 19th century. From these earlier changes, digital pianos are created in the late 1900s and soon hybrid pianos are made with both acoustic and digital features. Musical instrument evolution explains why Plotkin suggests listeners compare an original classical piece of music in a modern format. It may become emotively different from older recordings because of instrument focus in the music or change in the instrument of presentation. Plotkin notes there are experiential and interpretive differences in modern performances of the classics. Here is where an audio example would have been helpful.

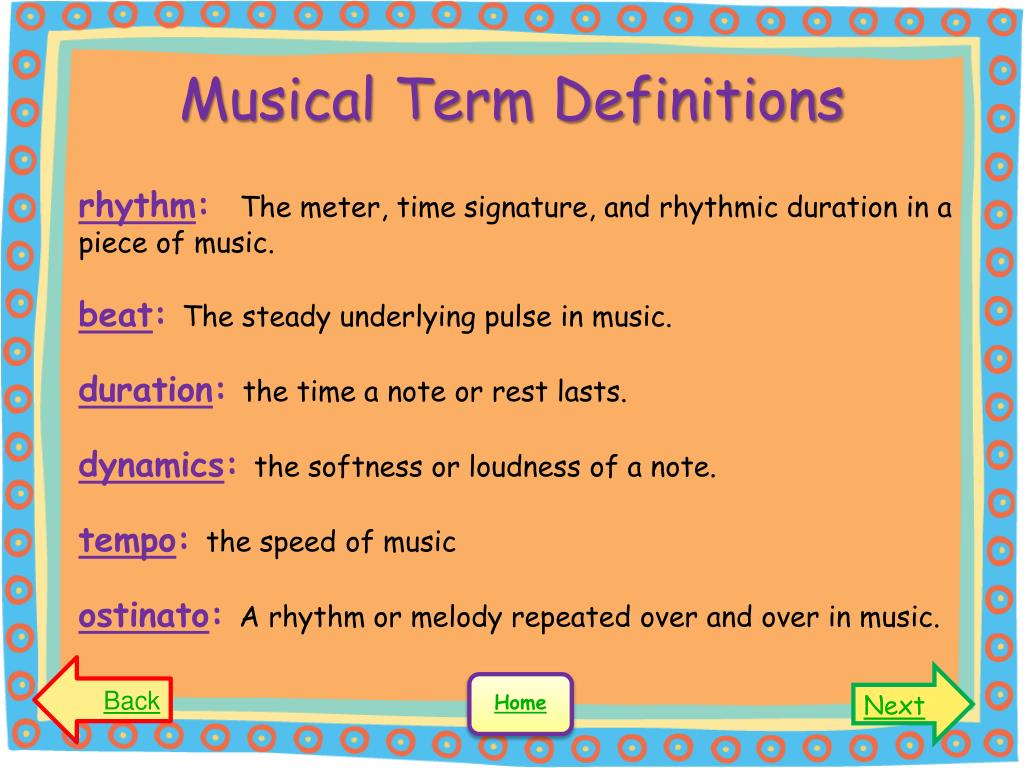

Plotkin notes that difference in musical performances go beyond changes in musical instruments. He notes interpretations of the classics change. He explains artists like Emanuel Ax and Marilyn Horne use tempo, and phrasings dynamics that offer different experiences to a listener. (Another example of why it would have been easier to understand if there was an audio example.) Plotkin endorses listening to recordings of musical productions because they offer clarity and access to a wider audience. However, Plotkin notes that a live performance offers more spontaneity and emotional immediacy than a recording.

It is feelings of a modern audience that excites Plotkin’s imagination

Plotkin makes the point that an historical original may or may not be the best that a composers’ creation offers to a modern audience. However, it is feelings of a modern audience that excites Plotkin’s imagination. In Plotkin’s opinion, a classics’ meaning is not to be cast in stone because times change, and yesterday’s history may not resonate with today’s events. What Plotkin is driving for is the cultivation of expert listeners who can appreciate yesterday’s classics because they resonate with today’s events, though composed in a different era, they offer new perspective to modern events.

One who has listened to both Greenberg’s lectures and Plotkin’s book recognize both want to reach an audience of non-specialists to nurture their interest in classical music.

Both believe classical music is an interpretive exercise based on an orchestra’s performance. They are peas in a pod when it comes to wanting to see emotional transformation in a person listening to a classic’s performance. Both Greenberg and Plotkin believe the classics are meant to be a sensual experience. Greenberg educates his audience on the structure and historical complexity of classical music. Plotkin focuses on classical musical instruments and performances that remain classics because of their emotive relevance to the present as well as the past.

Different points of view about classical music.

One presumes Greenberg’s and Plotkin’s two views of classical music may come into conflict in the changes from the original intent of great composers who have created what Greenberg may argue is a timeless masterpiece. Greenberg’s technical understanding of composition may seem more important than a transitory emotional response from a less knowledgeable audience. Here is where a detailed presentation of Beethoven’s ninth could have clarified the values of the classics noted in Plotkin’s excellent book. One wonders how a modern performance of Beethoven’s ninth might be different from an earlier version.

Value of musical classics.

Both Greenberg and Plotkin offer equal enlightenment on the value of musical classics. Audiences will always have different understandings of classical performances. The goal of a great classical performance is to please its audience. Pleasure in a classical performance can appeal to one who is familiar with the technical aspects of a production and to another for its emotional impact. Both Greenberg and Plotkin offer valuable insights to the relevance and reason for attending classical music performances in this ever-changing world.