Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Radical Candor (Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity)

Author: Kim Scott

Narrated By: Kim Scott

Kim Scott (Author, former executive at Apple and Google, coach for tech companies like Dropbox and Twitter)

The agricultural revolution dates back to 10,000 BCE, 1760 marks the beginning of the industrial revolution, the 1950s evolves into an age of expertise and work knowledge with computerization, in the 1990s connectivity and automation begins the information age. Today, Kim Scott addresses the 2020s along with the advent of artificial intelligence. Beginning when the industrial revolution takes hold, organization management evolves into a social science. In the industrial age training changes from demonstrating how to make things to managing people’s work in making things. Jumping to the Information Age managers of people become ringmasters for employee’s creativity.

Despite many changes in purpose for organizations a common thread is managerial skill which entails political and personal skills. Managers pursue understanding, influence, ability, and sincerity of purpose to elicit and manage human creativity.

Scott outlines management skills in “Radical Candor”. Her book is a useful tool for aspiring managers. Even reaching back to the agricultural age, there is relevance in Scott’s belief in “Radical Candor”. She defines radical candor as “Caring personally while challenging (organization employees) directly.” By personally caring, Scott explains good managers must gain the trust of people who report to them. My personal experience as a former manager in different careers shows that no manager knows everything about the company or organization they manage. The one thing a good manager must know is how to develop trust with people who report to her or him. Without trust between managers and workers, organizations are likely to fail.

Trust between managers and employees is even more true today because worker’ creativity drives technological invention and utility.

Being vulnerable by understanding you know nothing about people you manage is the starting point of your role as a manager. Scott explains the first thing a new manager must do is personally meet with each direct report to hear what they do for the organization, what they like and dislike about what they do, and what obstacles get in their way that impede accomplishment. The two-fold purpose of these meetings is first to listen, not judge or criticize what is being reported. The second is to build trust.

(I believe A.I. will always be a technological tool, not a controller, of society, contrary to those who believe human existence will be erased by machines. As a technological tool of humanity, the creativity of human minds is at the frontier of management change.)

Scott explains how important it is to let employees know their manager is interested in an employee’s goals and growth in an organization.

A manager must be both physically and emotionally present when building trust with an employee. There is a need for a manager to explain one’s own vulnerability and responsibility in managing others. Scott’s point is that gaining trust of an employee requires more than knowing their birthday. A good manager will ask for feedback about what an employee is doing and what support a manager can offer to improve their performance. A manager should be curious, not furious when things are not going well. It is important that a sense of respect be given for an employee’s effort to get their job done. With development of respect, it becomes possible to use radical candor to constructively criticize or complement an employees’ performance.

Scott notes there are many reasons for an employee’s failure to perform beyond expectations.

Those reasons include incompetence but also the failure of management to have a clear understanding of an employees’ strengths and weaknesses. Through development of trust between manager and employee, a different job may be in order. With reassignment and a performance plan, a manager may be able to tap a human resource that has been wasted. The performance plan is instituted with “Radical Candor” and offers either opportunity or, if performance improvement fails, dismissal.

Every organization has distinctive operational idiosyncrasies that a manager may not precisely understand.

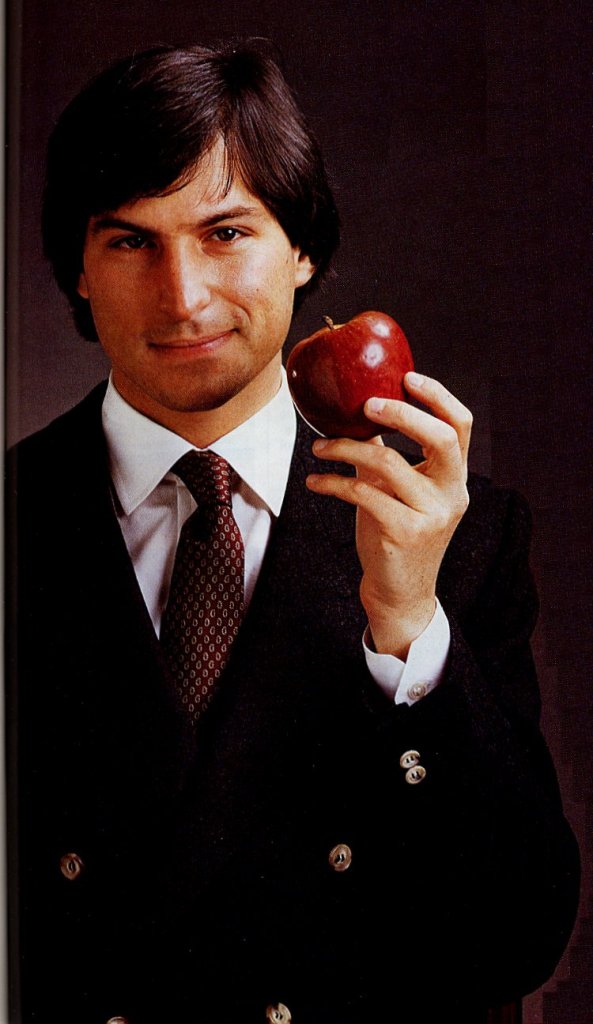

This has always been true. It is even more true in the tech age because project uniqueness and employee creativity is more difficult to measure and manage. Kim Scott has worked with the most iconic tech companies of modern times, e.g. Apple, Google, Twitter. There are a number of anecdotes about famous tech giants and officers of Facebook, Apple, and Google, like Sandberg, Cook, and Page. Kim has also started her own businesses, some of which failed, and others that prospered. Her experience offers credibility to her arguments.

From personal experience as a manager of others, no manager ever knows all there is to know.

As Scott notes, this is not to say that geniuses like Steve Jobs did not know more than his Apple employees, but the iPhone idea came from a group of employees before approaching Jobs with a clunky mock-up of the idea. Jobs had a reputation for being a tough audience for people with creative ideas. This is the reason Kim Scott explains trust must be created between manager and employee so that candor about needs and expectations can be usefully employed to improve probability of personal and organizational success.

One takes Kim Scott’s counsel on “Radical Candor” with some reservation because misused “Radical Candor” about a creative idea can discourage employee creativity. Scott’s counsel on building trust is her magic potion, but potions can kill as well as heal.