Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

The Perfectionists

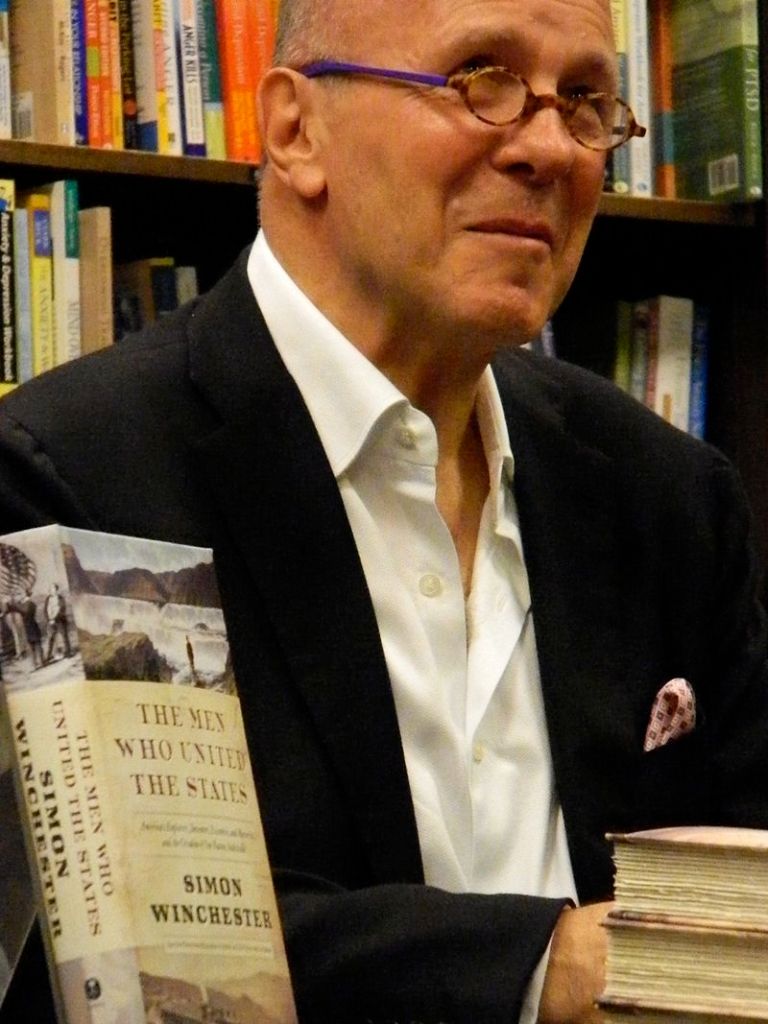

Author: Simon Winchester (How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World)

Narrated By: Simon Winchester

Simon Winchester (British-American author and journalist)

The beginning of “The Perfectionist” has an interesting vignette about Simon Winchester’s father that sets the table for his book. Simon’s father is characterized as an engineer that was asked to investigate why ammunition being used during WWII was misfiring. Bernard Winchester went to the production’ plant and precisely measured the ammunition that was being manufactured. Its quality was found to be well within specifications required to fire properly when used. Simon’s father followed a shipload of the ammunition to its destination to re-measure the specifications after delivery. The on-board jostling of cargo boxes caused miniscule damage to ammunition resulting in misfires in the field. Simon’s father’s discovery led to better packaging of the ammunition. Simon notes his father is highly praised by the military for his diligent investigation which made corrections in the way ammunition was packaged for transport to the front.

Simon’s father followed a shipload of ammunition to its destination to re-measure the specifications after delivery.

Simon Winchester’s story of his father is the subject of “The Perfectionist”. There are many ways of categorizing the advance of civilization. Manufacturing precision is Simon Winchester’s category of choice. Simon explains how improvements in precision, reaching as far back as the 18th century, led to technological advancement in the modern world. To Winchester, much of that advancement came from the needs of the military.

Winchester notes that John Wilkinson standardized and precisely measured cannon barrel rifling in the 1770s to improve accuracy.

The inaccuracy of weapons like cannons, mass production of reliable weaponry, and strategic advantage for military commands were founded on improvements in precision. Winchester notes that John Wilkinson standardized and precisely measured cannon borings in the 1770s to improve accuracy and reliability in battle. In the 1800s, the French began standardizing gun parts to allow interchangeability when field weapons were damaged or just quit working. In visiting France, Thomas Jefferson recognized the value of that interchangeability during America’s civil war when weapons often broke down and could only be repaired by craftsman who understood how a uniquely designed gun could be repaired.

Eli Whitney chose to hoodwink the American government during the War of Independence when he falsely claims to have a manufacturing plant that could produce standard gun parts.

Around 1801, Whitney contracts with the government and is paid but never produces any standardized parts. Whitney puts on a false show of interchangeability with parts that were manufactured by craftsman rather than a standardized process of production. (Whitney is neither penalized or required to repay the government.) The consequence of mass production of precise gun parts and ammunition is to kill more people in war which started an arms race that continues through to today. Progress in weapon design and manufacture is a harbinger of good and ill. Moving away from weapon production to the rise of industrialization, precise measurement remains a critical component of societies’ modernization.

Though there are precursors to the steam engine that reach back before the 18th century, James Watt (pictured here) revolutionizes its design with the help of Matthew Boulton.

Winchester explains how refinement of the steam engine enables the Industrial Revolution. Watt is obsessed with refining the containment of steam from an operating engine. Watt knows leakage of steam is correlated with loss of steam engine power and potential. The key to achieving better efficiency comes from John Wilkinson who develops a machine that could bore a precise hole through solid iron. With that level of precision, Watt recognized he could produce an engine with perfectly cylindrical, leak-proof chambers that could more efficiently power pistons to produce energy. Watt, Boulton, and Wilkinson open the world to the industrial revolution. Winchester suggests precision is the pursuit of perfection, i.e., a preeminent turning point in history. One may take issue with that conclusion because invention and innovation seem more important than precision, which is a tool rather than a cause for modernity.

The remarkable story of the jet engine is told by Winchester.

It is surprising that the jet engine became a reality as early as the beginning of WWII. Like nuclear bomb invention, Germany’s Hitler initially fails to grasp the importance of jet engine propulsion. However, Germany becoming the first to create a jet plane, the Heinkel He 178, to fly with jet propulsion. Hitler is more focused on refinement of the V-2 rocket as a revenge weapon against England than on jet propulsion for airplanes.

Frank Whittle (1907-1996, English aviation engineer and pilot who invented the jet engine.)

The original idea for the jet engine came from Frank Whittle, a British engineer in the early 1930s. Whittle realized Newton’s laws of energy could propel an airplane without propellers. Newton’s third law says for every action in one direction there is an equal but opposite energy reaction. Whittle acquired a patent on the idea of a jet engine but because of the five-pound cost of patent renewal and lack of any financial support for his brilliant idea, his patent expired. As a result, no single entity holds a patent on jet propulsion. It is not until May of 1941, that Frank Whittle’s turbojet engine first flies a plane.

1945 Gloster Meteor British jet.

There are many issues to be resolved for the idea of a jet engine to propel an airplane. There is the extreme pressure and heat generated by fuel being ignited within a turbine that must be designed with precise measurements, i.e., measurements within millionths of an inch. Winchester notes that the slightest deviation in blade shape, alignment, or material composition could cause vibration, inefficiency, or worse–engine failure and pilot death. The jet engine components had to endure extreme temperature changes and withstand metal fatigue while operating with high-speed rotating parts. Thousands of parts had to be precisely designed and integrated to provide the propulsion necessary for flight.

Whittle’s ultimate success leads him to be Knighted in 1948.

Whittle is recruited in 1937 by British Thomson-Houston, an engineering firm, to build a prototype of a jet engine. With money to create a prototype, Whittle turned his design idea into reality. With the help of two retired RAF officers, Whittle formed a company called Power Jets Ltd. In 1944, Britan nationalized Power Jets Ltd and Whittle was compelled to resign from the board in 1946. However, Whittle was ultimately recognized and knighted in 1948 for his contribution to Jet engine development.

The next big area of change addressed by Winchester is computer chip manufacture.

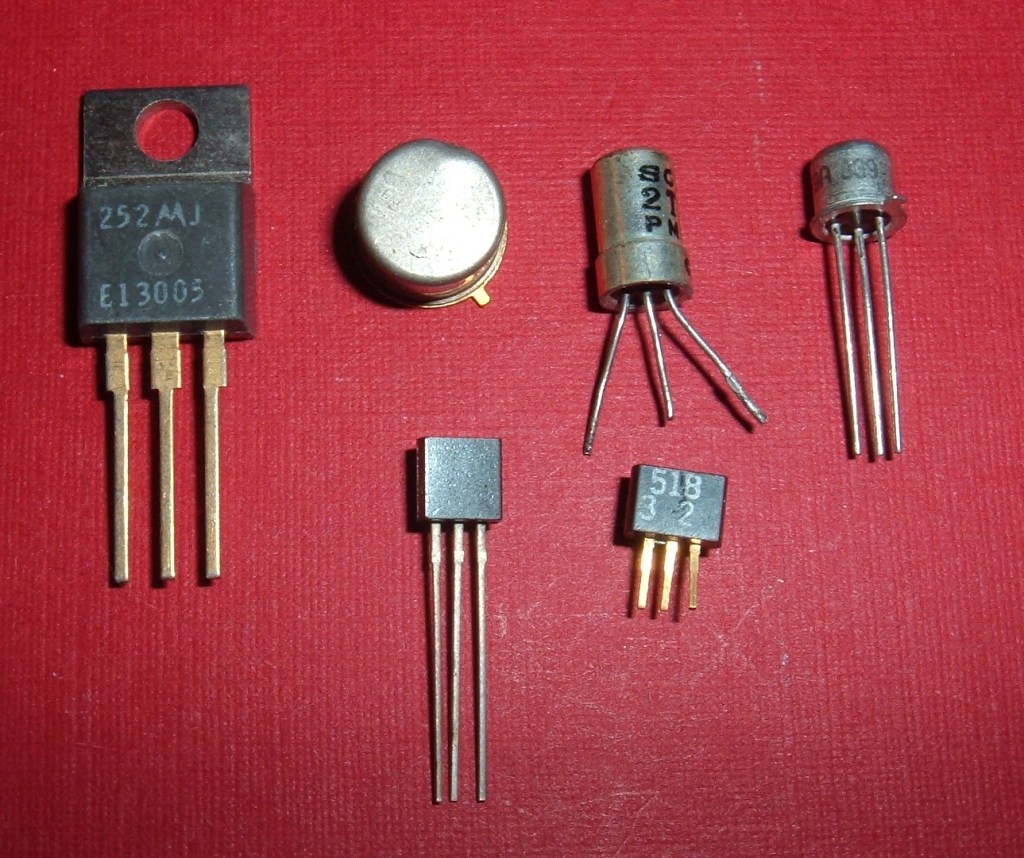

Transistors like these in the early years of computers are used in computer chip manufacture.

Winchester’s primary subject is Moore’s law postulated in 1965 by Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel. Moore predicts microchip computing power and efficiency would double every year and then every two years with continued miniaturization of chip transistors. His prediction, as of today, holds true. The size of computer chip transistors is measured in millimeters in the early 1960s. Today, measurement is at an atomic level, trending toward the use of quantum theory to continue Moore’s law prediction.

The last chapter of “The Perfectionist” is about measurement as a tool. Ironically, understanding measurement evolves through history. It may be a standard of change, but it is also a subject of change. The idea of distance measurement has evolved from an organic explanation that only imperfectly describes the visual world. That imperfectness leads to an obsession with exactness that boggles the mind.

As a caution, Winchester suggests the pursuit of precision may blind us to other values. The aesthetic beauty of a musical composition, architecture, a great novel, or mere thoughts of human beings may have little to do with precise measurement but can change the world. What one sees or feels is what we discount or respond to with emotion and/or appreciation, regardless of measurement analytics. Science is unquestionably dependent on precise measurement while art or literature may have little to do with it.