Books of Interest

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Understanding Japan (A Cultural History)

Lecturer: Mark J. Ravine

By: The Great Courses: Civilization & Culture

Mark J. Ravina (Professor of History at Emory University with an M.A. and Ph.D. from Stanford.)

In preparation for a trip to Japan this fall, it seems prudent to hear from someone who knows something about Japan’s culture and history. Professor Ravina specializes in Japanese history with focus on 18th and 19th century Japanese politics; however, these lectures go farther back and forward than his specialty. There is so much detail in these lectures, one is unable to fairly summarize what Ravina reveals.

Japan is an archipelago made up of 14,125 islands with 260 of which are occupied. The four main islands are Honshu (the home of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka), Hokkaido to the north, Kyushu to the south, and the smallest Shikoku (between Honshu and Kyushu).

Like the history of any nation that has existed since the 4th century CE, Japan’s culture has evolved based on influences that came from within and outside its borders. From indigenous beliefs to exposure to areas outside its territory, Japan has changed its traditions and culture. The rule of Japan has ranged from imperium to a battle-hardened warrior class to a popularly elected intellectual class influenced by internal and external societal and political events. At times, each social class has offered both stability and conflict. In the 20th century, of course, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor dramatically changed its economy and influenced its society.

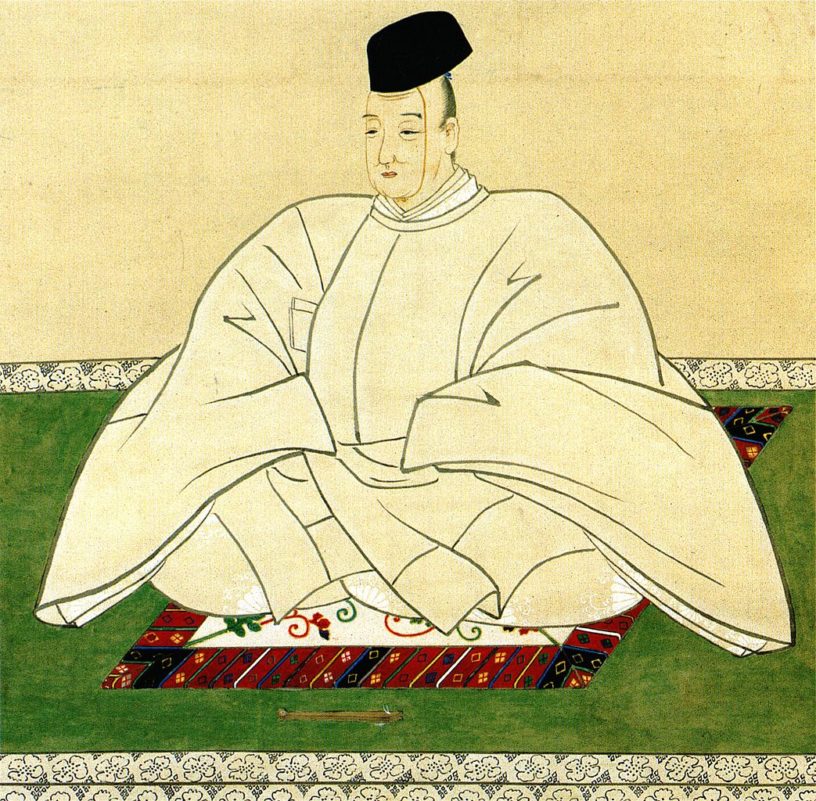

Japanese Emperor.

In Japan’s early centuries, an imperial and aristocratic class rose to rule Japan. The Asuka, Nara, Helan emperors during the Fujiwara era (538-1185) were respected and revered but the rise of the samurai class turned emperors into influencers more than exercisers of power. Power becomes centralized in a society that is highly stratified with nobility, Buddhist clergy, samurai, farmers, and artisans. Before 1185, territorial regents developed their own armies by relying on feudal lords who had their own warrior clans that became the fierce samurai of legend and reality.

As regents of Japan gained power and influence, emperors became symbols of culture more than centers of power. Rule and administration of territories became reliant on the power of a samurai class that at first supported the regents but soon became the true rulers of Japan.

Loyalty, honor, and focus on victory or death changed the management class and encouraged society to revere a Zen aesthetic, a belief in simplicity, naturalness, imperfection, and quiet depth. The samurai became a power behind the thrown in the 12th century and eventually the de facto rulers of Japan with emperors becoming more ceremonial. Leading samurai became Shoguns, hereditary military rulers of Japan. Emperors were revered, but their power diminished with growing influence of Shoguns that held power for nearly 700 years from 1185 to 1868.

Samurai leadership unified Japanese society.

Ravina explains the samurai period of Japan matured in the 12th century which evolved into rule by the strongest. Samurai influence shaped the political, social and philosophical identify of the people. In what is called the Edo period of the samurai from 1603 to 1868, there were long periods of peace and prosperity like that of the Tokugawa shogunate in the modern-day Tokyo area of Japan. The Edo period lasted for 250 years. Literacy grew during this period and was tied to governance, law, and moral instruction. Religious practices became more ritualized with meditation and subtlety different spiritual beliefs. A merchant class is formed during this period and the arts, like calligraphy and theatre performances, became more widely practiced. Kabuki theatre becomes an entertainment with a reputation ranging from the ethereal to debauched.

Ravina explains samurai values are not abandoned but are recast to focus on industrialization of Japan in the 19th century.

By the end of the ninetieth century, 95% of the citizens had been educated in schools, compared with just 3% in 1853. The samurai became leaders in modern institutions and businesses. They followed a samurai code called Bushido with core values of rectitude, courage, benevolence, respect, honesty, honor, loyalty, and self-control. Emphasis is put on living with purpose, discipline, and moral clarity.

A Japanese garden.

Ravina notes Japanese culture is exemplified by garden creations that represent the religious and philosophical ideals of its residents. The Japanese take great pride in their tea gardens, rock gardens, strolling gardens, some of which have become UNESCO heritage sites. The Japanese revere nature because it represents the Zen principles of simplicity, naturalness, imperfection, and the depth of a quiet life. Gardens are considered spiritual and moral spaces for quiet contemplation.

Ravina suggests Japan, like America and most nations of the world, has not abandoned its past but has adapted to the present based on what has happened in its past. Ravina’s history is helpful in preparing for a trip to Japan because it offers some basis for comparison and understanding.