Audio-book Review

By Chet Yarbrough

Blog: awalkingdelight

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

Long Walk to Freedom

By: Nelson Mandela

Narrated by: Michael Boatman

Nelson Mandela, (1918-2013, Died at age 95, South African anti-apartheid activist and politician, President of South Africa 1994-1999)

Nelson Mandela’s autobiography details the life of a remarkable and important leader of South Africa’s revolt against apartheid. Mandela began as a pacifist resister of white repression. However, his autobiography shows a change in belief from passive resistance to violence. (Mandela’s evolution from pacifist to belief in violence for social change is a reminder of the evolution of Malcolm X , the rise of the Black Panthers in America, and the Hamas and Israeli conflict in Palestine and Israel.)

Factions of the world today, like Mandela’s thought and action in the mid-20th century, believe in the utility of violence and terror for social change. The state of Israel, the territory of Gaza, and many countries of the world, like India, Lebanon, Iran, Hong Kong, Sudan, Libya, America, and others have political factions that believe they can change their societies with violence and terror. The conundrum of violence and terror is whether they proffer social gain or loss. The truth of gain or loss from violence and terror is being tested by the Hamas faction of Palestine and the conservative followers of Netanyahu in Israel.

The likelihood of a young African boy raised in a small village becoming President of South Africa beggars the imagination.

Mandela’s autobiography explains how it happened. There are 11 officially recognized tribes in South Africa. Mandela was born into the Thembu royal family, a subgroup of the Xhosa people. He explains his father, though not literate or formally educated, is a leader in his village. Mandela notes that his father had four wives and travelled between villages to spend time with each wife. When his father was away, his birth mother took care of him, but his father, as well as his mother, seem to have had great influence on his life. Mandela tells of walks with his father and the conversations his father has with other village members that mold Mandela’s beliefs and ambition in life.

Mandela notes his mother guides him to an important change in his life. When his father dies, his mother moves to a bigger village where he comes under the care of a regent of the Thembu tribe.

Mandela is effectively adopted into the royal Thembu family and moves into their palace. His ambition seems stimulated by that association and inspires him to become a formally educated South African.

Mandela receives a BA degree from Fort Hare in Alice, South Africa in 1943. He studied law at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. At that time, Mandela did not receive a law degree but was able to practice law because of a two-year diploma in law as an add-on to his BA. (When imprisoned, he studies, passes his University of South Africa’ law classes, and receives an LLB in 1989.) Mandela chooses to use his two-year diploma in law to become an advocate for Black liberation in South Africa. After graduation and his beginning practice of law, he is counseled by some to abandon politics to avoid arrest and intimidation by the government. However, Mandela chooses to join the African National Congress (ANC) in 1943. He becomes the co-founder of the youth league of ANC in 1944.

In his early ANC years, Mandela emphasized passive resistance like that practiced by Mahatma Gandhi in India. ANC had been formed in 1912 as a South African native congress but grew to become a multi-racial organization including all races and ethnic groups in South Africa. Mandela notes that the communist party was interested in being part of ANC’s role in liberating South Africans from apartheid. Mandela expresses reservation about the CPSA (the Communist Party of South Africa) but acknowledges its help in raising funds for an ANC army that was to be organized by Mandela as a militant resistance force to overcome apartheid. CPSA influence and ANC association became a part of the movement.

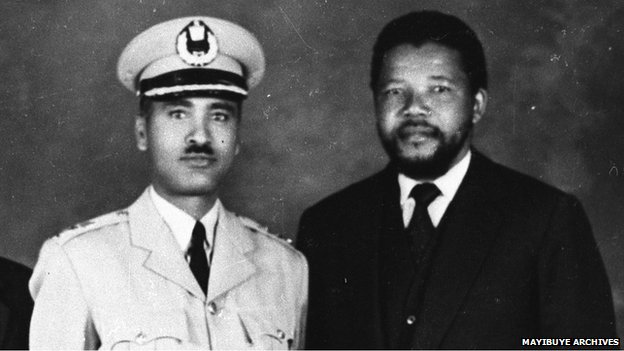

Mandela grows to believe political recognition requires violent resistance but also a personal ability to persuade others to join the ANC’ movement either financially or physically. Mandela is trained in Ethiopia by Col Fekadu Wakene on how to plant explosives and manage a volunteer army.

Col Fekadu Wakene taught South African political activist Nelson Mandela the tricks of guerrilla warfare – including how to plant explosives before slipping quietly away into the night. (BBC Africa by Penny Dale)

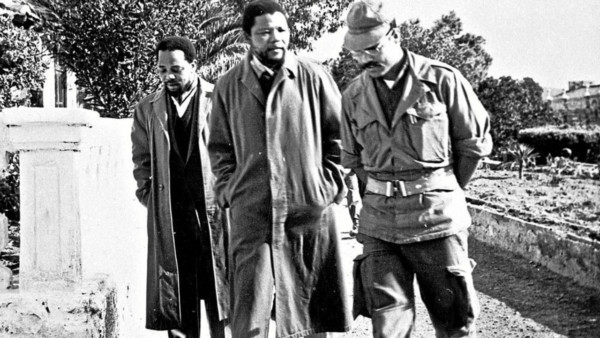

Ironically, Mandela is arrested in 1961 after only one action by his gathered volunteer army in December 1961. Whether the action is at the order of Mandela is not revealed but the resistance blows up an electricity sub-station. Mandela is arrested and serves 27+ years in prison for organizing the volunteer army which became known as Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation). Three years of trial led to a guilty verdict.

The last chapters of Mandela’s autobiography is about his incarceration on Robben Island and Pollsmoor Prison and the conditions of his imprisonment. While in prison, Mandela continues his education to become a licensed attorney.

In the first two years at Robben Island, Mandela and his co-conspirators are restricted to their cells. Methodist religious services were eventually allowed but sermonizing about reconciliation offended Mandela and his fellow prisoners. Though much of what some ministers preached were offensive to the imprisoned, Mandela approves of one minister who looks at his religion through the lens of science as well as faith.

Mandela and his co-conspirators remain at Robben Island for 18 years before being transferred to Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town. This is a significant improvement in their incarceration because of cell accommodations and food quality. However, his co-conspirators are separated from Mandela. Mandela is released in 1990, over 29 years after arrest.

Mandela explains a door is opened to the government of South Africa by Kobie Coetsee (1931-2000, died at age 69), the South African minister of justice and prisons.

In 1985, Botha was President of South Africa. Botha offered release to Mandela if he would unconditionally renounce violence against the government. Mandela refused and Botha denied Mandela’s release.

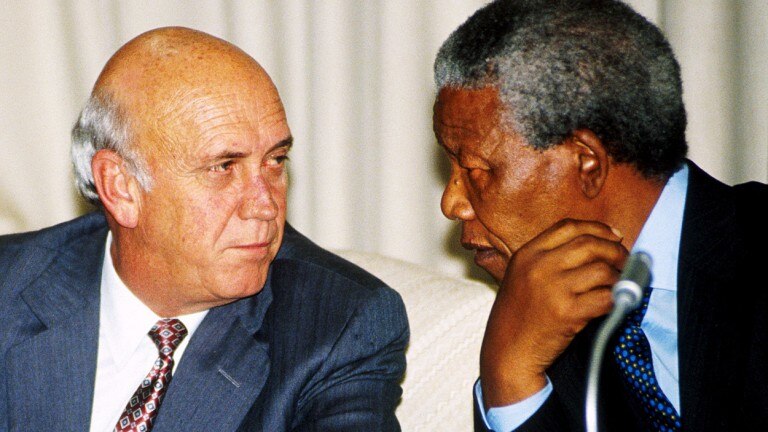

When F. W. de-Klerk became President of South Africa, after being Minister of National Education, a possibility for Mandela’s release was reopened.

Later, Mandela negotiated with de-Klerk to have his co-conspirators released from Robben Island and Pollsmoor. Further, Mandela negotiated with de-Klerk to have South Africa’s apartheid policies eliminated. President de-Klerk agreed, and Mandela was released in 1990. Both de-Klerk and Mandela receive the Nobel Peace prize for their negotiated peace agreement.

The last three-hour section of Mandela’s autobiography is about freedom and Mandela’s election as President of South Africa. The price of peace is high because violence seems a requirement for good-faith negotiation between opposing parties. Mandela’s biography and today’s conflict between Hamas and Israel makes one ask oneself–Is a tenuous and ephemeral peace worth the death of innocents?

(There is a brief interview with the author who aided Mandela in completion of his autobiography. It took two years of interviews and research to complete Mandela’s story.)