Audio-book Review

By Chet Yarbrough

Blog: awalkingdelight)

Website: chetyarbrough.blog

A World Beneath the Sands: The Golden Age of Egyptology

By: Toby Wilkinson

Narrated by: Graeme Malcolm

Toby Wilkinson (English Egyptologist and academic, former Fellow at Christ’s College Cambridge.)

Toby Wilkinson writes an enlightening introduction to ancient Egypt and its meaning for today’s Egyptians. The pre-modern age of Egypt reaches back to 3,200 or 3150 BCE with only southern Africa, China, and Mesopotamia appearing to have older artifacts discovered by archeologists. Long before Greek and Roman civilizations spread their beliefs around the Mediterranean and Africa, Egypt created dynasties that ruled large portions of the middle east.

Egypt’s ancient stories had been in plain sight for over 4000 years. Wilkinson notes it is not until the 19th century that Egyptian hieroglyphics are recognized as a written language. That language comes from a combination of pictures, symbols, and signs that represent words and sounds that tell the story of an estimated 170 pharaohs.

Hieroglyphics were initially presumed to be pictorial representations rather than words that tell the story of ancient Egypt. (A little independent research shows written language’ remnants have been found for older civilizations in Africa, China, and Mesopotamia. One wonders what cultural stories have been lost in their histories. Some ancient written documents are found in China but less in Africa and Mesopotamia.)

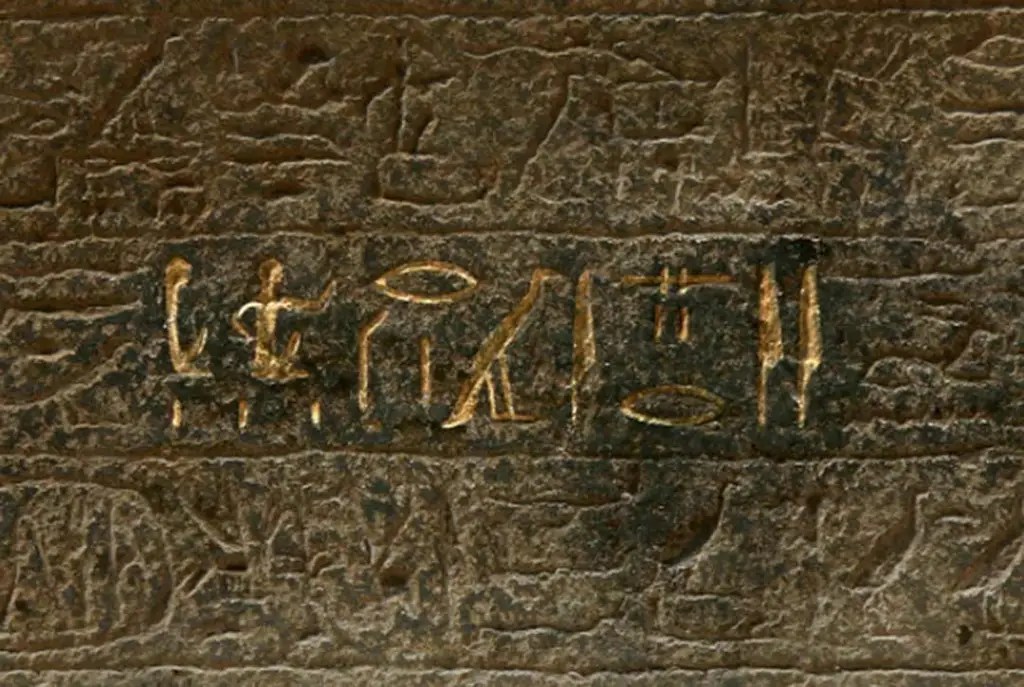

Sir Flinders Petrie uncovers the Merneptah Stele in 1896 in Thebes. The Stele is a 10-foot slab, presently exhibited in a Berlin, Germany museum. It reveals the name Merneptah, a pharaoh who reigned from 1218 to 1203 BCE.

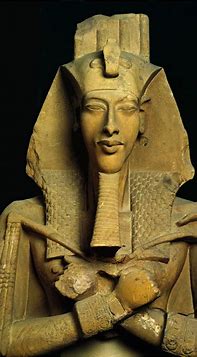

Narmer is the most ancient Pharoh identified in a hieroglyph. His reign is estimated to have been between 3273 and 2987 BCE. These are the language hieroglyphs identifying Narmer as the first known Pharoh.

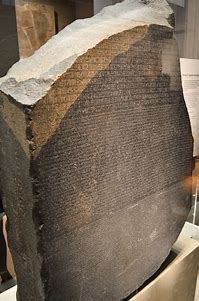

Wilkinson’s history reinforces the idea of written language’s importance to Arab culture. Of course, the most renown hieroglyphic message is on the Rosetta Stone which is an administrative decree written in 196 BC on behalf of King Ptolemy V. As is true of many ancient Egyptian artifacts, the stone is not in Egypt but in London which becomes a growing objection by modern Egyptians.

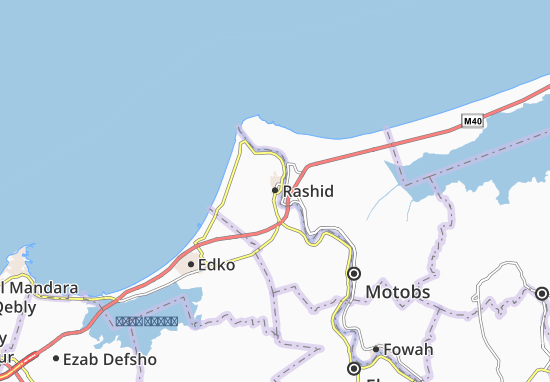

Pierre Bouchard, one of Bonaparte’s soldiers, found the Rosetta Stone at a fort near Rosetta overlooking the Mediterranean. When Napoleon is defeated in 1801, the terms of the Treaty of Alexandria gave the British the right to take the Rossetta Stone to England. (Presently shown in London at the Victoria and Albert Museum.)

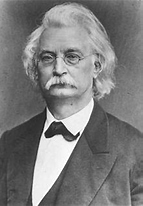

Thomas Young (1773-1829, British polymath and scientist who researched the physiology of light and contributed to later scientists, like Einstein, on the principle of light as a wave.)

The value of the stone is in its opening to a translation of ancient Egyptian language and history. Dr. Thomas Young, a storied English polymath, examines the stone to analyze its meaning. Though Young did not recognize it as a language, his initial research confirmed earlier research by a French Egyptologist named Jean-Francois Champollion. Later, Champollion discovered hieroglyphics are actually an Egyptian language drawn from different written languages. With that realization, a history of Egypt becomes open to the world. The names of former Pharaohs, some of their beliefs, acts, and dates of rule become known.

Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac (1790-1832, died at the age of 41, French philologist.)

Around 1205 BCE , the word “Israel” is shown in Egyptian hieroglyphics. This is during the reign of Pharaoh Merneptah of Egypt’s 19th dynasty, the successor to Ramses II. The inference is that Israel was a political entity far back in the ancient history of the middle east.

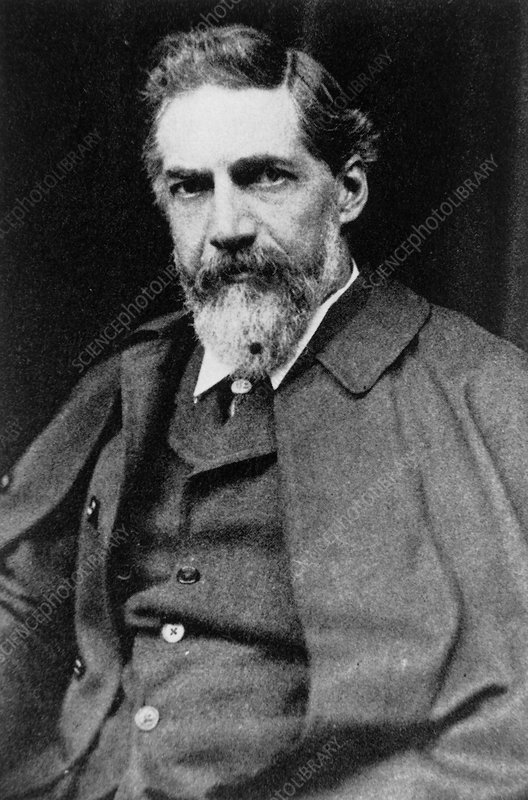

John Gardner Wilkinson, English traveler, writer and pioneer Egyptologist from 1797-1875 “Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians” published in 1837. He was knighted in 1839 as the first distinguished British Egyptologist. (Interestingly, though the same last name as the author, they are not believed to be related.)

An interesting point noted by Wilkinson is that Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion in 1798 is a critical turning point in research and knowledge of ancient Egypt. Bonaparte’s purported reason for Egypt’s invasion is to protect French trade interests and to undermine Britain’s access to India and the East Indies.

Having traveled to Egypt in 2019, we visited the fort in which the Rosetta Stone was found. The fort is on the Mediterranean in the city of Rashid, sometimes referred to as Rosetta, or el-Rashid, a port city where the Nile flows into the Mediterranean.

Champollion becomes the curator of the Egyptian collection at the Louvre in 1826 and returns to Egypt in 1828 on an archeological expedition to become the chair of Egyptian antiquities at the College of France in 1831. Champollion writes a dictionary for hieroglyphic translation and a “Primer of the Hieroglyphic System of the Ancient Egyptians”.

The Louvre today with its pyramid addition at its entrance is a reminder of France’s role in revealing ancient Egypt’s history.

After Young and Champollion’s great discoveries about hieroglyphs, the reign of Muhammed Ali becomes a particular interest of Wilkinson’s history of Egypt between 1805 and 1848. The relationship between France and Egypt during Ali’s reign, with the help of hieroglyphs’ research of Champollion, much of Egypt’s history is discovered.

Toby Wilkinson notes Muhammad Ali (1769-1849) was an Ottoman Turkish military leader who became the pasha and viceroy of Egypt in 1805 with world recognition in 1842.

Pasha Ali modernizes Egypt with advertent, as well as inadvertent, help of France and England. In 1827, Ali sends two giraffes as gifts to France. In 1830, France invades Algeria which Ali views as a threat to his rule. Ali responds by building up Egypt’s military. Ali wages war against the Ottoman Empire (from which he came) to capture Constantinople in 1840. Europe intervenes and brokers a peace in 1842 by making Ali and his descendants recognized hereditary rulers of Egypt and Sudan. Ali uses his newly recognized independence by France and England to modernize Egypt.

Ali is considered the founder of modern Egypt. He and his heirs rule Egypt until 1952. Ali introduced many reforms to modernize Egypt’s economy, society, and military. He added to Egypt’s territory with the invasion of Syria, Arabia, Sudan and Anatolia but his rise to power is halted by a coalition of Britain, France, Russia, and Austria between 1840 and ’41. Ali had become a threat to the balance of power in Europe. The coalition offers heredity rule of Egypt and Sudan to Ali to cease his aggressive action against what was then part of the Ottoman Empire. Ali rules until his death in 1849 when his grandson, Abbas I, becomes ruler of Egypt and Sudan.

Abas I, ruled from 1848-1854. He undid much of what Muhammed Ali had done to modernize Egypt. Some historians suggest Abas plundered Egypt and Sudan and allowed the infrastructure of Egypt to decay.

Before Ali’s death, he manages to create a new class of Egyptians by abolishing a feudal land system with a redistribution of land to former peasants. Cotton and sugarcane become major Egyptian exports. Ali reforms the military and creates a modern army and navy along European lines. He encourages industrialization with education of the young in a secular school system.

Jean-Francois Champollion becomes world famous for deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. He finds hieroglyphics are an amalgamated pictorial and Coptic language that reveals the history and rulers of ancient Egypt. Thomas Young, an English polymath contributes to the translation of hieroglyphics but concedes its fundamental revelations to Champollion. Wilkinson’s fundamental point is that Napoleon opens the door to Egyptology, the scientific study of ancient Egypt.

The French philologist Jean-Francois Champollion accompanies Napoleon in the 1798 invasion of Egypt.

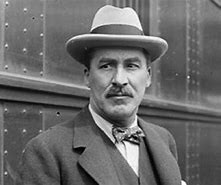

The irony of Wilkinson’s history is that Egyptology begins with French, English, German, and later–American interests. Egyptians just wished for a better life than what they were experiencing in their day-to-day existence before the 1920s. However, Atkinson notes the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb creates nationalist pride that remains a driving force in modern Egypt. In the early years, after Napoleone’s invasion, the citizens of Egypt were focused on making a living in a hard country with little interest or realization of their ancient culture and its importance in the history of civilization.

There are many names of French, English, German, and American researchers introduced by Atkinson. Some of the most important are (left to right) Jean-Francois Champollion, Thomas Young, Sir Flinders Petrie, Karl Richard Lepsius, and Howard Carter.

The legacy of Egypt’s ancient civilization awakened a nationalist fervor among Egyptians that expelled French, English, German, and American Egyptologists that contributed knowledge of Egypt’s ancient history but confiscated many ancient Egyptian artifacts. Wilkinson argues Tutankhamen’s discovery triggered change in Egyptian nationalism. As a result of Carter’s surprising 1922 discovery of Tutankhamen’s burial site in the Valley of the Kings, Tutankhamen became a rallying cry for Egyptian independence and recognition. Whether it was the trigger for Egyptian pride in their heritage or not is somewhat irrelevant. The truth of Wilkinson’s history is that ancient Egypt was one of the great nations of the world that may once again rise to prominence.